diff --git a/.gitignore b/.gitignore

new file mode 100644

index 0000000..eda0a58

--- /dev/null

+++ b/.gitignore

@@ -0,0 +1 @@

+res/Thumbs.db

diff --git a/01-Introduction.md b/01-Introduction.md

index 9bfa836..363d5aa 100644

--- a/01-Introduction.md

+++ b/01-Introduction.md

@@ -1,2 +1,146 @@

-Introduction

+序言

============================

+

+在五年级的时候,我和我的小伙伴们被获准使用一个容放着一些非常破旧的 TRS-80s (译者注:见[维基百科TRS-80s](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TRS-80)) 的废弃教室。为了激励我们,一个老师找到了一些简单的 BASIC 程序的打印输出让我们鼓捣玩耍。

+

+电脑上的音频盒式磁带驱动器当时是坏掉的,所以每次我们想要运行一些代码的时候,我们不得不仔细的从头开始键入。这使得我们更喜欢那些只有几行代码的程序:

+

+```

+10 PRINT "BOBBY IS RADICAL!!!"

+20 GOTO 10

+```

+> 注解

+

+> 如果计算机打印足够多的次数,或许它会神奇的变成现实哦。(译者注:这里指的是计算机反复打印第10行代码的语句`BOBBY IS RADICAL!!!`,作者开玩笑的说会变成现实。)

+

+即便如此,整个过程还是比较艰辛。我们不懂得如何去编程,所以一个小的语法错误便让我们感到很费解。程序出毛病是家常便饭,而那是我们只能重头再来。

+

+在有了这些小程序的经验积累之后,我们遇到了个大BOSS:一个代码密密麻麻占去好几页纸的程序。我们光是鼓起勇气决定去尝试它就花了不少时间,光是它的标题“隧道与巨人”("Tunnels and Trolls")就令人捉摸不透。这听起来像是个游戏,而还有什么事比亲手编写一款电脑游戏更酷?

+

+我们从没让它实际运行起来过。一年后,我们搬出了那个教室。(后来随着我更多地接触BASIC,才意识到它只是一个为桌面游戏使用的角色生成器,而并非整个游戏。)但木已成舟,从那之后,我立志要成为一个游戏开发者。

+

+在我十几岁时,我的家人搞了一台装有 QuickBASIC 的 Macintosh,之后又装了 THINK C。我几乎整个暑假都在那上面倒腾游戏。自学是缓慢而痛苦的。我希望能让程序轻松地跑一些功能-一张地图或者是个小的猜谜游戏-但是随着程序的扩大,这越来越难了。

+

+> 注解

+

+> 我的许多夏天都是在路易斯安那州南部的沼泽中捕蛇和乌龟来渡过的。如果户外不是这样酷热,很有可能,这将是一本爬虫学的书,而不是编程书。

+

+起初,我的挑战在于让程序跑起来。后来,我开始思考如何让程序做一些超越我脑袋所想的工作。除了阅读一些关于“如何用C++编程”的书籍,我开始试图寻找一些关于如何组织程序的书籍。

+

+又过了几年,一个朋友给了我一本书:《设计模式:可复用面向对象软件的基础》。终于来了!这就是我从青少年开始便一直寻找的那本书!我们刚碰面,我就把书从头到尾读了一遍。我之前仍然在为我自己写的程序挣扎犯愁,但是看到别人也如此挣扎并提出了解决方案,我便解脱了。我感觉我终于有了一些武器用来挥舞而不再是赤手空拳了。

+

+> 注解

+

+> 这是我们第一次见面,5分钟自我介绍之后,我坐在他的沙发上,并在接下来的几个小时里,我聚精会神地阅读而完全忽视了他。我感觉那时候自己的社交能力还是稍有那么一丁点提升的。

+

+在2001年,我得到了我梦想中的工作:EA(Electronic Arts) 的软件工程师。我迫不及待的想看下真正的游戏,以及工程师是如何组织它们的。像 Madden Football 这样的大型游戏到底是一个什么样的架构?他们是怎么让一套代码库在不同平台上运行的?

+

+破解开放的源码是一个震撼人心和令人惊奇的体验。图形、人工智能、动画和视觉效果等各个方面的代码都十分出众。我们公司有人懂得如何榨取CPU的每一个周期并得以善用。甚至一些我认为不可能的东西,这些家伙一个早上就能搞定。

+

+但这种优秀代码的结构往往是事后想出来的。他们太专注于功能以至于忽视了组织架构。模块之间耦合很严重。只要是有作为的新功能都会被扔进代码库里。我的幻想破灭了,在我看来,恐怕很多程序员,从没翻过_设计模式_,不曾了解[单例模式](02.5-Singleton.md)。

+

+当然,实际并非想象的那么糟。我曾设想游戏程序员们坐在放满白板的象牙塔中,从头到尾的几周时间里都在想当然地讨论代码架构细节。实际上,我所见到的代码是出自那些被上司催着进度的人之手。他们竭尽了全力,而且,我逐渐意识到,他们竭尽全力的结果往往是很棒的。我越深入这些代码,便越是这么觉得。

+

+不幸的是,“隐藏”一词恰恰反映了这样的情况:宝藏埋在代码深处,而许多人只从地表踏过。我看到同事在努力重塑更好的解决方案时,他们所寻求的办法正藏在他们脚下的代码库之中。

+

+这样的问题正是这本书所关注的。我挖掘并打磨出自己在游戏中所发现的最好的设计模式,在此一一呈现给大家,以便我们将时间节省下来发现新大陆,而不是重新造轮子。

+

+# 市面上的书籍

+

+目前市面已经有数十多本游戏编程的书籍。为什么还要再写一本?

+

+我见过的大多数游戏编程书籍无非下列两类:

+

+- __关于特定领域的书籍__。这些针对性较强的书籍为你的游戏开发打开一个独特而深刻的视角。他们会教你3D图形,实时渲染,物理模拟,人工智能,或音频处理。这些是多数游戏程序员在自己的职业生涯中所专注的领域。

+

+- __关于整个游戏引擎的书籍__。相反,这些书尝试涵盖整个游戏引擎的各部分。它们被组织起来形成一个完整的引擎以适用于一些特定类型的游戏,通常是3D第一人称射击游戏。

+

+我喜欢这两类书,但我觉得它们仍留有一些空白。特定领域的书很少会写你的代码块如何与游戏的其他部分交互。你可能擅长物理和渲染(译者注:这里指的是在某个领域特别擅长的人),是你知道如何优雅的将它们拼合起来?

+

+第二类书籍写到了这些,但我通常发现这类书都太单一,太泛泛而谈。特别是随着移动和休闲游戏的兴起,我们正处在充斥着大量不同类型游戏的时代。我们不再只是克隆 Quake(译者注:雷神之锤,第一个真3D实时演算的FPS游戏)了。当你的游戏不适合这个模型时,这类阐述单个引擎的书籍就不再合适了。

+

+相反,这里我想要做的,更倾向于“引导”。在这本书中,每个章节都是一个独立的思想,而你可以将它应用到你的代码里。藉此,你可以混用它们以令其在你制作的游戏中发挥最好的效果。

+

+> 注解

+

+> 这种“向导”风格的另外一个例子,就是广受大家喜爱的《游戏编程精粹》系列。

+

+# 设计模式相关

+

+任何名字中带有“模式”的编程书籍都和经典图书《设计模式:可复用面向对象软件的基础》脱不了干系。这本书由 Erich Gamma,Richard Helm,Ralph Johnson 和 John Vlissides 完成。(俗称“Gang of Four”--四人组)

+

+> 注解

+

+> 设计模式一书本身也源自前人的灵感。使用模式语言来描述开放式解决问题的想法来自[《A Pattern Language》](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Pattern_Language),由 Christopher Alexander(以及Sarah Ishikawa,Murray Silverstein)完成。

+

+> 他们的书是关于架构(就像真正的建筑结构有着建筑和围墙之类的东西),但他们希望他人会使用相同的结构来描述在其他领域的解决方案。设计模式(Design Patterns)是 Gang of Four 在软件领域的一个尝试。

+

+本书以“游戏编程模式”命名,并不是说 Gang of Four 的书不适用于游戏。恰恰相反,在[再探设计模式](02-Design Patterns Revisited.md)一节中覆盖众多来自GoF著作的设计模式,同时强调了在游戏开发中的运用。

+

+从另一面说,我觉得这本书也适用于非游戏软件。我也可以把这本书命名为 _More Design Patterns_,但我认为游戏制作例子更吸引人。难道你真的想要阅读的一本关于员工记录和银行账户例子的书么?

+

+话虽这么说,这里介绍的模式在其他软件中是有用的,我觉得他们是特别适合于软件开发,就像在游戏中经常遇到的挑战一样:

+

+- 时间和序列化往往是一个游戏的架构的核心部分。事情必须依照正确的顺序和正确的时间发生。

+

+- 开发周期被高度压缩,程序员们需要能够快速构建和迭代一组丰富且相异的行为,同时不牵涉到他人或者弄乱代码库。

+

+- 所有这些行为被定义后,游戏便开始互动。怪物撕咬英雄,药水混合在一起,炸弹炸到敌人和朋友...诸如此类。这些交互必须很好地进行下去,同时代码库需要保持干净不能纷乱无章得像个交织错乱的毛线球。

+

+- 最后,性能是游戏的关键。游戏开发者们总在不断比赛着看谁能够充分利用平台的性能。游戏周期处理的不同可能意味着产品是成为数以百万计销售的A级游戏,或者满是掉帧且贴满愤怒评论的废铁。

+

+# 如何阅读本书

+

+_游戏编程模式_分为三大部分。第一部分是序言和书的概括。这正是你现在阅读的章节以及[下一章节](01.1-Architecture, Performance, and Games.md)。

+

+第二部分,再探设计模式,回顾了 Gang of Four 中的一些设计模式。在每个章节中,我会提及自己对该模式的认识,及将该模式运用到游戏中的方法。

+

+最后部分是这本书的重头戏。这部分代表了我认为十分有用的13种设计模式。它们分为四类:序列模式,行为模式,解耦模式,优化模式。

+

+这些模式使用一致的文本组织结构来讲述,以便你将该书作为参考并能快速找到你所需要的内容:

+

+- __目的__ 部分简述了此模式旨在解决的问题。这样你很容易根据自己遇到的问题来快速确定该用哪个模式。

+

+- __动机__ 部分描述了一个示例、该示例存在问题、我们将要对之采用设计模式。不同于具体的算法,模式通常是无形的,除非针对一些特定的问题。学设计模式离不开示例正如学烘培离不开面团一样。这个部分提供面团,之后的部分将会教你如何烘培。

+

+- __模式__ 部分会提炼出前面示例中的模式本质。如果你想了解该模式的书面描述,就是这部分了。如果你已经熟悉了,这部分也是一个很好的复习,确保你没有忘记该模式。

+

+- 到目前为止,该模式只是就一个单一的例子来解释的。但你怎么该模式是否适用于你的问题呢?__使用情境__ 针对模式使用的情境以及何时避免使用它提供一些指引。__使用须知__ 部分会指出使用该模式时面临的后果和风险。

+

+- 如果像我一样,需要借助具体的实例才能真正的理解,那么__示例__ 正满足你的需要。示例会一步步实现模式,所以你可以清楚的看到模式是如何工作的。

+

+- 模式和单一的算法不同,因为模式是开放式的。每次使用模式的时候,你实现的方式有可能会不同。接下来__设计决策__ 部分,会探讨这个问题,并告诉你在应用模式时要考虑的不同因素。

+

+- 结束部分,__参考__ 部分会告诉你该模式和其他模式的关联并指出使用该模式的一些真实世界中的开源代码。

+

+# 关于示例代码

+

+这本书中的示例代码用 C++ 编写,但是这并不意味着这些模式仅在该语言中有用或者说 C++ 比其他语言要好。几乎所有的语言都适用,虽然有些模式确实倾向于面向对象语言。

+

+我选择 C++ 有几个原因。首先,它是商业游戏中最流行的语言,是该行业的通用语言。 另外,C++ 基于 C 的语法也是 Java,C#,JavaScript和许多其他语言的基础。即使你不懂 C++,也没有关系,你可以很轻松的明白示例代码的含义。

+

+这本书的目的,不是教你学习 C++。示例会尽可能保持简单,但是这并不代表良好的 C++ 编码风格或使用就是这样。阅读代码时要理解代码所传达的思想,而不是代码本身的表达。

+

+特别一提的是,示例代码没有采用“现代” C++ -- C++11 或更高版本风格。它没使用标准库并很少使用模板。这是“糟糕”的 C++ 代码,但我仍希望保留下来,这样会对那些从C,Objective-C,Java和其他语言转来的人们更加的友好。

+

+为了避免浪费页面空间,你已经看到了,和模式不相关的代码,有时会在例子中省略,通常用省略号来表示省去的代码。

+

+举个例子,有一个函数,它会处理一些工作,并且会返回一个值。被解释的模式是只关心返回值,不关心处理的工作。在这种情况下,示例代码看起来像这样:

+

+```c++

+bool update()

+{

+ // Do work...

+ return isDone();

+}

+```

+# 下一步

+

+模式是软件开发中一个不断变化和扩展的部分。这本书从 Gang of Four 文献开始,并分享他们了解的软件设计模式,当书页发布之后过程仍然会继续。

+

+你是这个过程的核心部分。只要你开发了你自己的模式并细化(或者反驳!)这本书中提到的模式,你就是在为软件社区贡献力量。如果你关于书中内容有任何建议,修正或者其他反馈,请与我联系。

+

+===============================

+[目录](README.md#目录)

+

+[下一节](01.1-Architecture, Performance, and Games.md)

diff --git a/01.1-Architecture, Performance, and Games.md b/01.1-Architecture, Performance, and Games.md

index 294b180..368fd3e 100644

--- a/01.1-Architecture, Performance, and Games.md

+++ b/01.1-Architecture, Performance, and Games.md

@@ -1,2 +1,201 @@

Architecture, Performance, and Games

============================

+

+Before we plunge headfirst into a pile of patterns, I thought it might help to give you some context about how I think about software architecture and how it applies to games. It may help you understand the rest of this book better. If nothing else, when you get dragged into an argument about how terrible (or awesome) design patterns and software architecture are, it will give you some ammo to use.

+

+> note: Note that I didn’t presume which side you’re taking in that fight. Like any arms dealer, I have wares for sale to all combatants.

+

+# What is Software Architecture?

+

+If you read this book cover to cover, you won’t come away knowing the linear algebra behind 3D graphics or the calculus behind game physics. It won’t show you how to alpha-beta prune your AI’s search tree or simulate a room’s reverberation in your audio playback.

+

+> note:Wow, this paragraph would make a terrible ad for the book.

+

+Instead, this book is about the code between all of that. It’s less about writing code than it is about organizing it. Every program has some organization, even if it’s just “jam the whole thing into main() and see what happens”, so I think it’s more interesting to talk about what makes for good organization. How do we tell a good architecture from a bad one?

+

+I’ve been mulling over this question for about five years. Of course, like you, I have an intuition about good design. We’ve all suffered through codebases so bad, the best you could hope to do for them is take them out back and put them out of their misery.

+

+> note:Let’s admit it, most of us are responsible for a few of those.

+

+A lucky few have had the opposite experience, a chance to work with beautifully designed code. The kind of codebase that feels like a perfectly appointed luxury hotel festooned with concierges waiting eagerly on your every whim. What’s the difference between the two?

+

+## What is good software architecture?

+

+For me, good design means that when I make a change, it’s as if the entire program was crafted in anticipation of it. I can solve a task with just a few choice function calls that slot in perfectly, leaving not the slightest ripple on the placid surface of the code.

+

+That sounds pretty, but it’s not exactly actionable. “Just write your code so that changes don’t disturb its placid surface.” Right.

+

+Let me break that down a bit. The first key piece is that architecture is about change. Someone has to be modifying the codebase. If no one is touching the code — whether because it’s perfect and complete or so wretched no one will sully their text editor with it — its design is irrelevant. The measure of a design is how easily it accommodates changes. With no changes, it’s a runner who never leaves the starting line.

+

+## How do you make a change?

+

+Before you can change the code to add a new feature, to fix a bug, or for whatever reason caused you to fire up your editor, you have to understand what the existing code is doing. You don’t have to know the whole program, of course, but you need to load all of the relevant pieces of it into your primate brain.

+

+> note: It’s weird to think that this is literally an OCR process.

+

+We tend to gloss over this step, but it’s often the most time-consuming part of programming. If you think paging some data from disk into RAM is slow, try paging it into a simian cerebrum over a pair of optical nerves.

+

+Once you’ve got all the right context into your wetware, you think for a bit and figure out your solution. There can be a lot of back and forth here, but often this is relatively straightforward. Once you understand the problem and the parts of the code it touches, the actual coding is sometimes trivial.

+

+You beat your meaty fingers on the keyboard for a while until the right colored lights blink on screen and you’re done, right? Not just yet! Before you write tests and send it off for code review, you often have some cleanup to do.

+

+> note: Did I say “tests”? Oh, yes, I did. It’s hard to write unit tests for some game code, but a large fraction of the codebase is perfectly testable.

+

+> I won’t get on a soapbox here, but I’ll ask you to consider doing more automated testing if you aren’t already. Don’t you have better things to do than manually validate stuff over and over again?

+

+You jammed a bit more code into your game, but you don’t want the next person to come along to trip over the wrinkles you left throughout the source. Unless the change is minor, there’s usually a bit of reorganization to do to make your new code integrate seamlessly with the rest of the program. If you do it right, the next person to come along won’t be able to tell when any line of code was written.

+

+In short, the flow chart for programming is something like:

+

+

+

+> note: The fact that there is no escape from that loop is a little alarming now that I think about it.

+

+## How can decoupling help?

+

+While it isn’t obvious, I think much of software architecture is about that learning phase. Loading code into neurons is so painfully slow that it pays to find strategies to reduce the volume of it. This book has an entire section on decoupling patterns, and a large chunk of Design Patterns is about the same idea.

+

+You can define “decoupling” a bunch of ways, but I think if two pieces of code are coupled, it means you can’t understand one without understanding the other. If you de-couple them, you can reason about either side independently. That’s great because if only one of those pieces is relevant to your problem, you just need to load it into your monkey brain and not the other half too.

+

+To me, this is a key goal of software architecture: minimize the amount of knowledge you need to have in-cranium before you can make progress.

+

+The later stages come into play too, of course. Another definition of decoupling is that a change to one piece of code doesn’t necessitate a change to another. We obviously need to change something, but the less coupling we have, the less that change ripples throughout the rest of the game.

+

+# At What Cost?

+

+This sounds great, right? Decouple everything and you’ll be able to code like the wind. Each change will mean touching only one or two select methods, and you can dance across the surface of the codebase leaving nary a shadow.

+

+This feeling is exactly why people get excited about abstraction, modularity, design patterns, and software architecture. A well-architected program really is a joyful experience to work in, and everyone loves being more productive. Good architecture makes a huge difference in productivity. It’s hard to overstate how profound an effect it can have.

+

+But, like all things in life, it doesn’t come free. Good architecture takes real effort and discipline. Every time you make a change or implement a feature, you have to work hard to integrate it gracefully into the rest of the program. You have to take great care to both organize the code well and keep it organized throughout the thousands of little changes that make up a development cycle.

+

+> note: The second half of this — maintaining your design — deserves special attention. I’ve seen many programs start out beautifully and then die a death of a thousand cuts as programmers add “just one tiny little hack” over and over again.

+

+> Like gardening, it’s not enough to put in new plants. You must also weed and prune.

+

+You have to think about which parts of the program should be decoupled and introduce abstractions at those points. Likewise, you have to determine where extensibility should be engineered in so future changes are easier to make.

+

+People get really excited about this. They envision future developers (or just their future self) stepping into the codebase and finding it open-ended, powerful, and just beckoning to be extended. They imagine The One Game Engine To Rule Them All.

+

+But this is where it starts to get tricky. Whenever you add a layer of abstraction or a place where extensibility is supported, you’re speculating that you will need that flexibility later. You’re adding code and complexity to your game that takes time to develop, debug, and maintain.

+

+That effort pays off if you guess right and end up touching that code later. But predicting the future is hard, and when that modularity doesn’t end up being helpful, it quickly becomes actively harmful. After all, it is more code you have to deal with.

+

+> note: Some folks coined the term “YAGNI” — You aren’t gonna need it — as a mantra to use to fight this urge to speculate about what your future self may want.

+

+When people get overzealous about this, you get a codebase whose architecture has spiraled out of control. You’ve got interfaces and abstractions everywhere. Plug-in systems, abstract base classes, virtual methods galore, and all sorts of extension points.

+

+It takes you forever to trace through all of that scaffolding to find some real code that does something. When you need to make a change, sure, there’s probably an interface there to help, but good luck finding it. In theory, all of this decoupling means you have less code to understand before you can extend it, but the layers of abstraction themselves end up filling your mental scratch disk.

+

+Codebases like this are what turn people against software architecture, and design patterns in particular. It’s easy to get so wrapped up in the code itself that you lose sight of the fact that you’re trying to ship a game. The siren song of extensibility sucks in countless developers who spend years working on an “engine” without ever figuring out what it’s an engine for.

+

+# Performance and Speed

+

+There’s another critique of software architecture and abstraction that you hear sometimes, especially in game development: that it hurts your game’s performance. Many patterns that make your code more flexible rely on virtual dispatch, interfaces, pointers, messages, and other mechanisms that all have at least some runtime cost.

+

+> note: One interesting counter-example is templates in C++. Template metaprogramming can sometimes give you the abstraction of interfaces without any penalty at runtime.

+

+> There’s a spectrum of flexibility here. When you write code to call a concrete method in some class, you’re fixing that class at author time — you’ve hard-coded which class you call into. When you go through a virtual method or interface, the class that gets called isn’t known until runtime. That’s much more flexible but implies some runtime overhead.

+

+> Template metaprogramming is somewhere between the two. There, you make the decision of which class to call at compile time when the template is instantiated.

+

+There’s a reason for this. A lot of software architecture is about making your program more flexible. It’s about making it take less effort to change it. That means encoding fewer assumptions in the program. You use interfaces so that your code works with any class that implements it instead of just the one that does today. You use observers and messaging to let two parts of the game talk to each other so that tomorrow, it can easily be three or four.

+

+But performance is all about assumptions. The practice of optimization thrives on concrete limitations. Can we safely assume we’ll never have more than 256 enemies? Great, we can pack an ID into a single byte. Will we only call a method on one concrete type here? Good, we can statically dispatch or inline it. Are all of the entities going to be the same class? Great, we can make a nice contiguous array of them.

+

+This doesn’t mean flexibility is bad, though! It lets us change our game quickly, and development speed is absolutely vital for getting to a fun experience. No one, not even Will Wright, can come up with a balanced game design on paper. It demands iteration and experimentation.

+

+The faster you can try out ideas and see how they feel, the more you can try and the more likely you are to find something great. Even after you’ve found the right mechanics, you need plenty of time for tuning. A tiny imbalance can wreck the fun of a game.

+

+There’s no easy answer here. Making your program more flexible so you can prototype faster will have some performance cost. Likewise, optimizing your code will make it less flexible.

+

+My experience, though, is that it’s easier to make a fun game fast than it is to make a fast game fun. One compromise is to keep the code flexible until the design settles down and then tear out some of the abstraction later to improve your performance.

+

+# The Good in Bad Code

+

+That brings me to the next point which is that there’s a time and place for different styles of coding. Much of this book is about making maintainable, clean code, so my allegiance is pretty clearly to doing things the “right” way, but there’s value in slapdash code too.

+

+Writing well-architected code takes careful thought, and that translates to time. Moreso, maintaining a good architecture over the life of a project takes a lot of effort. You have to treat your codebase like a good camper does their campsite: always try to leave it a little better than you found it.

+

+This is good when you’re going to be living in and working on that code for a long time. But, like I mentioned earlier, game design requires a lot of experimentation and exploration. Especially early on, it’s common to write code that you know you’ll throw away.

+

+If you just want to find out if some gameplay idea plays right at all, architecting it beautifully means burning more time before you actually get it on screen and get some feedback. If it ends up not working, that time spent making the code elegant goes to waste when you delete it.

+

+Prototyping — slapping together code that’s just barely functional enough to answer a design question — is a perfectly legitimate programming practice. There is a very large caveat, though. If you write throwaway code, you must ensure you’re able to throw it away. I’ve seen bad managers play this game time and time again:

+

+> Boss: “Hey, we’ve got this idea that we want to try out. Just a prototype, so don’t feel you need to do it right. How quickly can you slap something together?”

+

+> Dev: “Well, if I cut lots of corners, don’t test it, don’t document it, and it has tons of bugs, I can give you some temp code in a few days.”

+

+> Boss: “Great!”

+

+A few days pass…

+

+> Boss: “Hey, that prototype is great. Can you just spend a few hours cleaning it up a bit now and we’ll call it the real thing?”

+

+You need to make sure the people using the throwaway code understand that even though it kind of looks like it works, it cannot be maintained and must be rewritten. If there’s a chance you’ll end up having to keep it around, you may have to defensively write it well.

+

+> note: One trick to ensuring your prototype code isn’t obliged to become real code is to write it in a language different from the one your game uses. That way, you have to rewrite it before it can end up in your actual game.

+

+# Striking a Balance

+

+We have a few forces in play:

+

+1. We want nice architecture so the code is easier to understand over the lifetime of the project.

+2. We want fast runtime performance.

+3. We want to get today’s features done quickly.

+

+> note: I think it’s interesting that these are all about some kind of speed: our long-term development speed, the game’s execution speed, and our short-term development speed.

+

+These goals are at least partially in opposition. Good architecture improves productivity over the long term, but maintaining it means every change requires a little more effort to keep things clean.

+

+The implementation that’s quickest to write is rarely the quickest to run. Instead, optimization takes significant engineering time. Once it’s done, it tends to calcify the codebase: highly optimized code is inflexible and very difficult to change.

+

+There’s always pressure to get today’s work done today and worry about everything else tomorrow. But if we cram in features as quickly as we can, our codebase will become a mess of hacks, bugs, and inconsistencies that saps our future productivity.

+

+There’s no simple answer here, just trade-offs. From the email I get, this disheartens a lot of people. Especially for novices who just want to make a game, it’s intimidating to hear, “There is no right answer, just different flavors of wrong.”

+

+But, to me, this is exciting! Look at any field that people dedicate careers to mastering, and in the center you will always find a set of intertwined constraints. After all, if there was an easy answer, everyone would just do that. A field you can master in a week is ultimately boring. You don’t hear of someone’s distinguished career in ditch digging.

+

+> note: Maybe you do; I didn’t research that analogy. For all I know, there could be avid ditch digging hobbyists, ditch digging conventions, and a whole subculture around it. Who am I to judge?

+

+To me, this has much in common with games themselves. A game like chess can never be mastered because all of the pieces are so perfectly balanced against one another. This means you can spend your life exploring the vast space of viable strategies. A poorly designed game collapses to the one winning tactic played over and over until you get bored and quit.

+

+# Simplicity

+Lately, I feel like if there is any method that eases these constraints, it’s simplicity. In my code today, I try very hard to write the cleanest, most direct solution to the problem. The kind of code where after you read it, you understand exactly what it does and can’t imagine any other possible solution.

+

+I aim to get the data structures and algorithms right (in about that order) and then go from there. I find if I can keep things simple, there’s less code overall. That means less code to load into my head in order to change it.

+

+It often runs fast because there’s simply not as much overhead and not much code to execute. (This certainly isn’t always the case though. You can pack a lot of looping and recursion in a tiny amount of code.)

+

+However, note that I’m not saying simple code takes less time to write. You’d think it would since you end up with less total code, but a good solution isn’t an accretion of code, it’s a distillation of it.

+

+> note: Blaise Pascal famously ended a letter with, “I would have written a shorter letter, but I did not have the time.”

+

+> Another choice quote comes from Antoine de Saint-Exupery: “Perfection is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.”

+

+> Closer to home, I’ll note that every time I revise a chapter in this book, it gets shorter. Some chapters are tightened by 20% by the time they’re done.

+

+We’re rarely presented with an elegant problem. Instead, it’s a pile of use cases. You want the X to do Y when Z, but W when A, and so on. In other words, a long list of different example behaviors.

+

+The solution that takes the least mental effort is to just code up those use cases one at a time. If you look at novice programmers, that’s what they often do: they churn out reams of conditional logic for each case that popped into their head.

+

+But there’s nothing elegant in that, and code in that style tends to fall over when presented with input even slightly different than the examples the coder considered. When we think of elegant solutions, what we often have in mind is a general one: a small bit of logic that still correctly covers a large space of use cases.

+

+Finding that is a bit like pattern matching or solving a puzzle. It takes effort to see through the scattering of example use cases to find the hidden order underlying them all. It’s a great feeling when you pull it off.

+

+# Get On With It, Already

+

+Almost everyone skips the introductory chapters, so I congratulate you on making it this far. I don’t have much in return for your patience, but I’ll offer up a few bits of advice that I hope may be useful to you:

+

+- Abstraction and decoupling make evolving your program faster and easier, but don’t waste time doing them unless you’re confident the code in question needs that flexibility.

+

+- Think about and design for performance throughout your development cycle, but put off the low-level, nitty-gritty optimizations that lock assumptions into your code until as late as possible.

+

+> note: Trust me, two months before shipping is not when you want to start worrying about that nagging little “game only runs at 1 FPS” problem.

+

+- Move quickly to explore your game’s design space, but don’t go so fast that you leave a mess behind you. You’ll have to live with it, after all.

+

+- If you are going to ditch code, don’t waste time making it pretty. Rock stars trash hotel rooms because they know they’re going to check out the next day.

+

+- But, most of all, if you want to make something fun, have fun making it.

\ No newline at end of file

diff --git a/02-Design Patterns Revisited.md b/02-Design Patterns Revisited.md

index da8acd6..5da234b 100644

--- a/02-Design Patterns Revisited.md

+++ b/02-Design Patterns Revisited.md

@@ -1,2 +1,23 @@

-Design Patterns Revisited

+再探设计模式

============================

+

+《设计模式:可复用面向对象软件的基础》一书已经出版了将近20年。不过通过阅读本章,你将有机会重温和理解设计模式。软件行业发展迅速,这本书确实有些古老了。这本书经久不衰说明比起许多框架和方法来说,设计模式更加永恒。

+

+然而我认为设计模式到了今天仍然重要,我们从过去几十年中学习到了许多东西。在这个章节中,我们将重温四人帮(Gang of Four)的几个原作设计模式。针对每一种模式,我都希望能写出一些有用、有趣的东西。

+

+我认为有些模式被过度使用([单例模式]()),而另一些却又被冷落([命令模式]())。书中还涉及到两个,我想探讨他们与游戏的相关性([享元模式](02.2-Flyweight.md)和[观察者模式](02.3-Observer.md))。最后,有时候我只是觉得了解设计模式在更大点的编程领域的表现是蛮有趣的([原型模式](02.4-Prototype.md)和[状态模式](02.6-State.md))。

+

+## 模式

+- [命令模式](02.1-Command.md)

+- [享元模式](02.2-Flyweight.md)

+- [观察者模式](02.3-Observer.md)

+- [原型模式](02.4-Prototype.md)

+- [单例模式](02.5-Singleton.md)

+- [状态模式](02.6-State.md)

+

+===============================

+[上一节](01.1-Architecture, Performance, and Games.md)

+

+[目录](README.md#目录)

+

+[下一节](02.1-Command.md)

diff --git a/02.1-Command.md b/02.1-Command.md

index 508d625..721dcc0 100644

--- a/02.1-Command.md

+++ b/02.1-Command.md

@@ -1,2 +1,412 @@

-Command

+命令模式

============================

+# 目的

+

+命令模式是我最喜爱的模式之一。在我写过的许多大型游戏或者其他程序中,都有用到它。正确的使用它,会让你的代码变得更加优雅。对于这个模式,Gang of Four 有着一个预见性的深奥说明:

+

+> 将一个请求(request)封装成一个对象,从而让你使用不同的请求,请求队列或请求日志来参数化客户端,同时支持请求操作的撤销与恢复。

+

+我想你也和我一样觉得这句话晦涩难明。首先,它分割了自己试图建立的物象。在软件世界之外,一词往往多义。“客户(client)”就是一个_人_的意思-一个你与它做生意的人。据我查证,人类(human beings)是不可“参数化”的。(译者注:作者在这里的意思是Gang of Four 的说明因为太具概括性,涵盖了软件开发之外的一些定义,使得句子很难理解。)

+

+然后,句子的剩余部分就像你可能使用的模式的一串列表一样。不是特别明朗,除非你的用例恰巧在列表中。我对命令模式的精炼(pithy)概括如下:

+

+__命令就是一个对象化(实例化)的方法调用。__(A command is a reified method call.)

+

+当然,“精炼”(pithy)通常意味着“令人费解的简洁”,所以我可能改得不是很好。让我解释一下:你可能没听过“Reify”一词,意即“具象化”(make real)。另一个术语reifying的意思是 使一些事物成为“第一类”(first-class)。(译者注:你可能在其他书籍中见到说是“[第一类值](http://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%AC%AC%E4%B8%80%E9%A1%9E%E7%89%A9%E4%BB%B6)”的类似说法)

+

+> 注解

+

+> “Reify”出自拉丁文“res”,意思为“thing”,加上英语后缀“-fy”,所以就成为了“thingify”,坦白说,这是个很有趣的单词。

+

+这两个术语都意味着,将某个_概念_(concept)转化为一块_数据_(data),即一个对象,你可以认为是传入函数的变量等等。所以说命令模式是一个“对象化的方法调用”,我的意思就是封装在一个对象的一个方法调用。

+

+你可能对“回调“(callback),”第一类函数“(first-class function),”函数指针“(function pointer),”闭包“(closure),。”局部函数“(partially applied function)更耳熟,至于耳熟哪个就取决于你所使用的语言,而它们都具共性。The Gang of Four 之后这样阐述:

+

+```

+命令就是回调的面向对象化。(Commands are an object-oriented replacement for callbacks.)

+```

+

+这个比他们对模式的概括要好多了。

+

+> 注解

+

+> 一些语言的_反射系统_(译者注: 如.NET)可以让你在运行时使用类型处理。你可以得到一个对象,它代表着某些其他对象的类,你也可以玩玩看类型可以处理哪些问题。换句话说,反射是一个具体化的类型系统。

+

+但是这些都比较抽象和模糊。正如我所推崇的那样,我喜欢用一些具体点的东西来开头。为弥补这点,现在开始我将举例,它们都非常适合命令模式。

+

+#动机

+

+# 输入配置

+

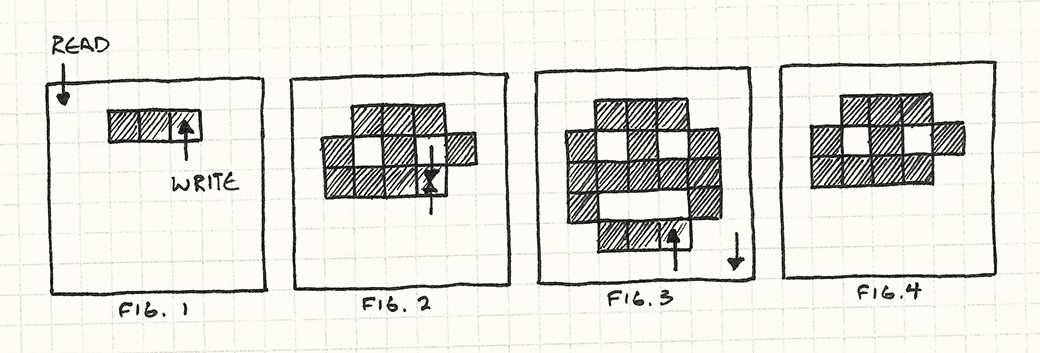

+每个游戏都有一处代码块用来读取用户原始输入-按钮点击,键盘事件,鼠标点击,或者其他等等。它记录每次的输入,并将之转换为游戏中一个有意义的动作(action):

+

+

+

+> 注解

+

+> 专业级贴士:请勿常按B键。

+

+下面是个简单的实现:

+

+```c++

+void InputHandler::handleInput()

+{

+ if (isPressed(BUTTON_X)) jump();

+ else if (isPressed(BUTTON_Y)) fireGun();

+ else if (isPressed(BUTTON_A)) swapWeapon();

+ else if (isPressed(BUTTON_B)) lurchIneffectively();

+}

+```

+这个函数通常会通过[游戏循环](03.2-Game Loop.md)被每帧调用,我想你能理解这段代码在干些什么。如果我们将用户的输入硬关联到游戏的动作(game actions),上面的代码是有效的,但是许多游戏允许用户_配置_他们的按钮与动作的映射。

+

+为了支持自定义配置,我们需要把那些对`jump()`和`fireGun()`的直接调用转换为我们可以换出(swap out)的东西。”换出“(swapping out)听起来很像分配变量,所以我们需要个_对象_来代表一个游戏动作。这就用到了命令模式。

+

+我们定义了一个基类用来代表一个可激活的游戏命令:

+

+```c++

+class Command

+{

+public:

+ virtual ~Command() {}

+ virtual void execute() = 0;

+};

+```

+

+> 注解

+

+> 当你的接口仅有一个无返回值的方法时,很有可能就会用到命令模式。

+

+然后我们为每个不同的游戏动作创建一个子类:

+

+```c++

+class JumpCommand : public Command

+{

+public:

+ virtual void execute() { jump(); }

+};

+

+class FireCommand : public Command

+{

+public:

+ virtual void execute() { fireGun(); }

+};

+

+// You get the idea...

+```

+在我们的输入处理中,我们为每个按钮存储一个指针指向他们。

+

+```c++

+class InputHandler

+{

+public:

+ void handleInput();

+

+ // Methods to bind commands...

+

+private:

+ Command* buttonX_;

+ Command* buttonY_;

+ Command* buttonA_;

+ Command* buttonB_;

+};

+```

+现在输入处理成了下面这样:

+

+```c++

+void InputHandler::handleInput()

+{

+ if (isPressed(BUTTON_X)) buttonX_->execute();

+ else if (isPressed(BUTTON_Y)) buttonY_->execute();

+ else if (isPressed(BUTTON_A)) buttonA_->execute();

+ else if (isPressed(BUTTON_B)) buttonB_->execute();

+}

+```

+

+> 注解

+

+> 注意到我们这里没有检查命令是否为`null`没?这里假设了每个按钮有某个命令与之对应关联。

+

+> 如果你想要支持不处理任何事情的按钮,而不用明确检查是否为null,我们可以定义一个命令类,这个命令类中的`execute()`方法不做任何事情。然后,我们将按钮处理器(button handler)指向一个空对象(null object)代替指向null。这个模式叫[空对象(Null Object)](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Null_Object_pattern)。

+

+以前每个输入都会直接调用一个函数,现在则会有一个间接调用层。

+

+

+

+简而言之,这就是命令模式。如果你已经看到了它的优点,不妨看完本章的剩余部分。

+

+# 模式

+

+# 关于角色的说明

+

+我们刚才定义的命令类在上个例子中是有效的,但他们很受限。问题在于,他们假设存在`jump()`,`fireGun()`等这样的能找到玩家的头像,使得玩家像木偶一样进行动作处理的顶级函数。

+

+这种假设耦合限制了这些命令的的效用。__JumpCommand__类_唯一_能做的事情就是使得 player 进行跳跃。让我们放宽限制。我们传进去一个我们想要控制的对象而不是用命令对象自身来调用函数:

+

+```c++

+class Command

+{

+public:

+ virtual ~Command() {}

+ virtual void execute(GameActor& actor) = 0;

+};

+```

+这里,__GameActor__是我们用来表示游戏世界中的角色的”游戏对象“类。我们将它传入`execute()`中,以便子类化的命令可以针对我们选择的角色进行调用,就像这样:

+

+```c++

+class JumpCommand : public Command

+{

+public:

+ virtual void execute(GameActor& actor)

+ {

+ actor.jump();

+ }

+};

+```

+现在,我们可以使用这个类来让游戏中的任何角色进行来回跳动。在输入处理和记录命令以及调用正确的对象之间,我们缺少了一部分。首先,我们改变下`handleInput()`,像下面这样返回一个命令(commands):

+

+```c++

+Command* InputHandler::handleInput()

+{

+ if (isPressed(BUTTON_X)) return buttonX_;

+ if (isPressed(BUTTON_Y)) return buttonY_;

+ if (isPressed(BUTTON_A)) return buttonA_;

+ if (isPressed(BUTTON_B)) return buttonB_;

+

+ // Nothing pressed, so do nothing.

+ return NULL;

+}

+```

+它不能直接执行命令,因为它并不知道该传入那个角色对象。命令是一个具体化的调用,这里正是我们可以利用的地方-我们可以延迟调用。

+

+然后,我们需要一些代码来保存命令并且执行对玩家角色的调用。像下面这样:

+

+```c++

+Command* command = inputHandler.handleInput();

+if (command)

+{

+ command->execute(actor);

+}

+```

+假设`actor`是玩家角色的一个引用,这将会基于用户的输入来驱动角色,所以我们可以赋予角色与前例一致的行为。在命令和角色之间加入的间接层使得我们可以让玩家控制游戏中的任何角色,只需通过改变命令执行时传入的角色对象即可。

+

+在实践中,这并不是一个常见的功能,但是有一种情况却经常见到。迄今为止,我们只考虑了玩家驱动角色(player-driven character),但是对于游戏世界中的其他角色呢?他们由游戏的AI来驱动。我们可以使用相同的命令模式来作为AI引擎和角色的接口;AI代码部分提供命令(Command)对象用来执行。(译者注:`command->execute(AI对象);`)

+

+AI选择命令,角色执行命令,它们之间的解耦给了我们很大的灵活性。我们可以为不同的角色使用不同的AI模块。或者我们可以为不同种类的行为混合AI。你想要一个更加具有侵略性的敌人?只需要插入一段更具侵略性的AI代码来为它生成命令。事实上,我们甚至可以将AI使用到玩家的角色身上,这对于像游戏需要自动运行的demo模式是很有用的。

+

+通过将控制角色的命令作为第一类对象,我们便去掉了直接的函数调用这样的紧耦合。相反的,把它想象成一个队列或者一个命令流(queue or stream of commands):

+

+> 注解

+

+> 关于队列更多信息,见[事件队列](./05.2-Event Queue.md)

+

+

+

+> 注解

+

+> 为什么我感觉有必要通过图片来解释“流(stream)”呢?为什么它看起来就像一个管道(tube)一样?

+

+一些代码(输入处理(the input handler)或者AI)生成命令并将它们放置于命令流中,一些代码(发送者(the dispatcher)或者角色自身(actor))执行命令并且调用它们。通过中间的队列,我们解耦了一端的生产者和另一端的消费者。

+

+> 注解

+

+> 如果我们把这些命令_序列化_,我们便可以通过互联网发送数据流。我们可以把玩家的输入,通过网络发送到另外一台机器上,然后进行回放。这是多人网络游戏很重要的一块。

+

+# 撤销和重做(Undo and Redo)

+

+最后这个例子(译者注:作者指的是撤销和重做)是命令模的成名应用了。如果一个命令对象可以 _do_ 一些事情,那么应该可以很轻松的 _undo_(撤销) 它们。撤销这个行为经常在一些策略游戏中见到,在游戏中如果你不喜欢的话可以回滚一些步骤。在_创建_游戏时这是一个很常见的工具。如果你想让你的游戏设计师们讨厌你,最可靠的办法就是在关卡编辑器中不要提供撤销命令,让他们不能撤销不小心犯的错误。

+

+> 注解

+

+> 这里可能是我的经验之谈。

+

+如果没有命令模式,实现撤销是很困难的。有了它,小菜一碟啊。我们假定一个情景,我们在制作一款单人回合制的游戏,我们想让我们的玩家能够撤销一些行动以便他们能够更多的专注于策略而不是猜测。

+

+我们已经可以很方便的使用命令模式来抽象输入处理,所以每次对角色的移动要封装起来。例如,像下面这样来移动一个单位:

+

+```c++

+class MoveUnitCommand : public Command

+{

+public:

+ MoveUnitCommand(Unit* unit, int x, int y)

+ : unit_(unit),

+ x_(x),

+ y_(y)

+ {}

+

+ virtual void execute()

+ {

+ unit_->moveTo(x_, y_);

+ }

+

+private:

+ Unit* unit_;

+ int x_, y_;

+};

+```

+注意到这个和我们上一个命令不太相同。在上个例子中,我们想要_抽象_出命令,执行命令时可以针对不同的角色。在这个例子中,我们特别希望将命令_绑定_到移动的单位上。这个命令的实例不是一般性质的”移动某些物体“这样适用于很多情境下的的操作,在游戏的回合次序中,它是一个特定具体的移动。

+

+这凸显了命令模式在实现时的一个变化。在某些情况下,像我们的第一对的例子,一个命令代表了一个可重用的对象,表示_ a thing that can be done_(一件可完成的事情)。我们前面的输入处理程序仅针对单一的命令对象,并要求在对应按钮被按下的时候其`execute()`方法被调用。

+

+这里,这些命令更加具体。他们表示_a thing that can be done at a specific point in time_(一件可在特定时间点完成的事情)。这意味着每次玩家选择移动,输入处理程序代码都会创建一个命令实例。像下面这样:

+

+```c++

+Command* handleInput()

+{

+ // Get the selected unit...

+ Unit* unit = getSelectedUnit();

+

+ if (isPressed(BUTTON_UP)) {

+ // Move the unit up one.

+ int destY = unit->y() - 1;

+ return new MoveUnitCommand(unit, unit->x(), destY);

+ }

+

+ if (isPressed(BUTTON_DOWN)) {

+ // Move the unit down one.

+ int destY = unit->y() + 1;

+ return new MoveUnitCommand(unit, unit->x(), destY);

+ }

+

+ // Other moves...

+

+ return NULL;

+}

+```

+一次性命令的特质很快能为我们所用。为了撤销命令,我们定义了一个操作,每个命令类都需要来实现它:

+

+```c++

+class Command

+{

+public:

+ virtual ~Command() {}

+ virtual void execute() = 0;

+ virtual void undo() = 0;

+};

+```

+

+> 注解

+

+> 当然了,在没有垃圾回收的语言如C++中,这意味着执行命令的代码也要负责释放它们申请的内存。

+

+`undo()`方法会反转由对应的`execute()`方法改变的游戏状态。下面我们针对上一个移动命令加入了撤销支持:

+

+```c++

+class MoveUnitCommand : public Command

+{

+public:

+ MoveUnitCommand(Unit* unit, int x, int y)

+ : unit_(unit),

+ xBefore_(0),

+ yBefore_(0),

+ x_(x),

+ y_(y)

+ {}

+

+ virtual void execute()

+ {

+ // Remember the unit's position before the move

+ // so we can restore it.

+ xBefore_ = unit_->x();

+ yBefore_ = unit_->y();

+

+ unit_->moveTo(x_, y_);

+ }

+

+ virtual void undo()

+ {

+ unit_->moveTo(xBefore_, yBefore_);

+ }

+

+private:

+ Unit* unit_;

+ int xBefore_, yBefore_;

+ int x_, y_;

+};

+```

+注意到我们在类中添加了一些状态。当单位移动时,它会忘记它刚才在哪。如果我们要撤销移动,我们得记录单位的上一次位置,正是`xBefore_`和`yBefore_`变量的功能。

+

+> 注解

+

+> 这看起来挺像[备忘录模式](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Memento_pattern)的,但是我发现备忘录模式用在这里并不能有效的工作。因为命令试图去修改一个对象状态的一小部分,而为对象的其他数据创建快照是浪费内存。只手动存储被修改的部分相对来说就节省很多内存了。

+

+> [持久化数据结构](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Persistent_data_structure)是另一个选择。通过它们,每次对一个对象进行修改都会返回一个新的对象,保留原对象不变。通过这样明智的实现,这些新对象与原对象共享数据,所以比拷贝整个对象的代价要小的多。

+

+> 使用持久化数据结构,每个命令存储着命令执行前对象的一个引用,所以撤销意味着切换到原来老的对象。

+

+为了让玩家能够撤销一次移动,我们保留了他们执行的上一个命令。当他们敲击`Control-Z`时,我们便会调用`undo()`方法。(如果他们已经撤销了,那么会变为”重做“,我们会再次执行那个命令。)

+

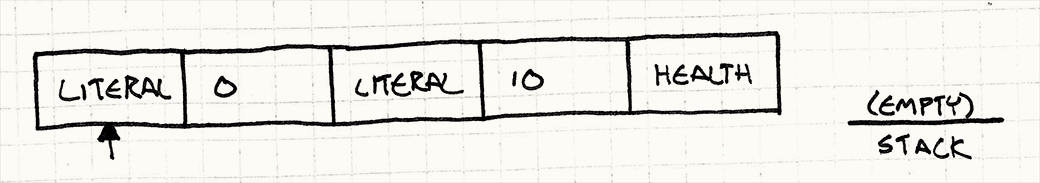

+支持多次撤销并不难。这次我们不再保存最后一个命令,取而代之的是,我们保存了一个命令列表和”current“(当前)命令的一个引用。当玩家执行了一个命令,我们将这个命令添加到列表中,并将”current“指向它。

+

+

+

+当玩家选择”撤销“时,我们撤销当前的命令并且将当前的指针移回去。当他们选择”重做“,我们将指针前移然后执行命令。如果他们在撤销之后选择了一个新的命令,列表中位于当前命令之后的所有命令被舍弃掉。

+

+我第一次在一个关卡编辑器中实现了这一点,顿时自我感觉良好。我很惊讶它是如此的简单而且高效。我们需要指定规则来确保每个数据的更改都经由一个命令实现,但只要定了规则,剩下的就容易得多。

+

+> 注解

+

+> 重做在游戏中并不常见,但回放(re-play)却不是。一个很老实的实现方法就是记录每一帧的游戏状态以便能够回放,但是这样会使用大量的内存。

+

+> 相反,许多游戏会记录每一帧每个实体所执行的一系列命令。为了回放游戏,引擎只需要运行正常游戏的模拟,执行预先录制的命令。

+

+#设计决策

+

+# 类风格化还是函数风格化?

+

+此前,我说命令(commands)和第一类函数或者闭包相似,但是这里我举的每个例子都用了类定义。如果你熟悉函数式编程,你可能想知道如何用函数式风格实现命令模式。

+

+我用这种方式写例子是因为 C++ 对于第一类函数的支持非常有限。函数指针无须过多阐述,仿函数(译者注:关于仿函数可以看[百科的介绍](http://baike.baidu.com/view/2070037.htm?fr=aladdin))看起来比较怪异,还需要定义一个类,C++11 中的闭包使用起来比较棘手因为要手动管理内存。

+

+这并不是说在其他语言中你不应该使用函数来实现命令模式。如果你使用的语言中有闭包的实现,无论怎样,使用它们!在某些方面(In some ways),命令模式对于没有闭包的语言来说是模拟闭包的一种方式。

+

+> 注解

+

+> 我说在某些方面(In some ways),是因为即使在有闭包的语言中为命令构建实际的类或结构仍然是有用的。如果你的命令有多个操作(如可撤销命令),映射到一个单一函数是比较尴尬的。

+

+> 定义一个实际的附带字段的类也有助于读者很容易分辨该命令中包含哪些数据。闭包自动包装一些状态是比较简洁,但它们太过于自动化了以至于很难分辨出它们实际上持有的状态。

+

+举个例子,如果我们在用 JavaScript 编写游戏,我们可以像下面这样创建一个单位移动命令:

+

+```js

+function makeMoveUnitCommand(unit, x, y) {

+ // This function here is the command object:

+ return function() {

+ unit.moveTo(x, y);

+ }

+}

+```

+我们也可以通过闭包来添加对撤销的支持:

+

+```js

+function makeMoveUnitCommand(unit, x, y) {

+ var xBefore, yBefore;

+ return {

+ execute: function() {

+ xBefore = unit.x();

+ yBefore = unit.y();

+ unit.moveTo(x, y);

+ },

+ undo: function() {

+ unit.moveTo(xBefore, yBefore);

+ }

+ };

+}

+```

+如果你熟悉函数式风格,上面这么做你会感到很自然。如果不熟悉,我希望这个章节能够帮助你了解一些。对于我来说,命令模式的作用能够真正的显示函数式编程在解决许多问题时是多么的高效。

+

+# 参考

+

+- 你可能最终会有很多不同的命令类。为了更容易地实现这些类,定义一个具体的基类,里面有着一些方便的高层次的方法,这样派生的命令可以将它们组合来定义自身的行为,这么做通常是有帮助的。它会将命令的主要方法`execute()`变成[子类沙盒](04.2-Subclass Sandbox.md)。

+- 在我们的例子中,我们明确地选择了那些角色会执行一个命令。在某些情况下,尤其是在对象模型是分层的情况下,它可能没这么直观。一个对象可以响应一个命令,或者它可以决定于关闭一些从属对象。如果你这样做,你需要了解下[责任链(Chain of Responsibility)](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chain-of-responsibility_pattern)。

+- 一些命令如第一个例子中的`JumpCommand`是一些纯行为的代码块,无需过多阐述。在类似情况下,拥有不止一个这样命令类的实例会浪费内存,因为所有的实例是等价的。[享元模式](02.2-Flyweight.md)就是解决这个问题的。

+

+> 注解

+

+> 你可以用[单例模式](02.5-Singleton.md)实现它,但我奉劝你别这么做。

+

+===============================

+[上一节](02-Design Patterns Revisited.md)

+

+[目录](README.md#目录)

+

+[下一节](02.2-Flyweight.md)

diff --git a/02.2-Flyweight.md b/02.2-Flyweight.md

index c71ced8..d0ec21c 100644

--- a/02.2-Flyweight.md

+++ b/02.2-Flyweight.md

@@ -1,2 +1,62 @@

-Flyweight

+享元模式

============================

+云雾散去,露出一片巨大而又古老、绵延的深林。数不清的远古铁杉,高出你而形成一个绿色的大教堂。叶子像彩色玻璃窗一样,将阳光打碎成一束束金黄色的雾气。巨大的树干之间,你能在远出制作出巨大的深林。

+对于我们游戏开发者来说,这是一种超凡脱俗的梦境设置,这样的场景我们经常通过一个模式来实现,它的名字可能并不常见,那就是享元模式。

+

+### 构成深林的树

+我能用简短的语句描述绵延不绝的深林,然而在一个虚拟现实游戏中去实现它却又是另一回事。当你看到各种形状不一的树填满整个屏幕时,在图形程序员眼里看到的,却是每隔60分之一秒就必须渲染进GPU的数以百万计的多边形。

+

+我们谈到成千上万的树,每一颗的几何结构又都包含了成千上万的多边形。即便你有足够的内存来描述这片深林,到了需要渲染的时候,这些数据还必须像搭乘巴士一样从CPU传输到GPU。

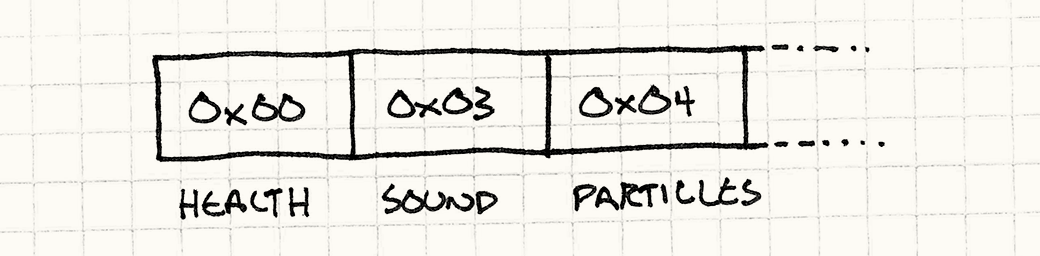

+ 每一颗树都有一堆与之相关联的数据:

+

+ * 交织成网状的定义了树的主干、树枝以及树叶的多边形。

+ * 树皮和树叶的贴图。

+ * 它在深林中的位置以及朝向。

+ * 大量的参数像大小、颜色等,这样每棵树看起来都不一样。

+

+如果你将它在代码中表述出来,那么你将得到下面的东西:

+

+ class Tree

+ {

+ private:

+ Mesh mesh_;

+ Texture bark_;

+ Texture leaves_;

+ Vector position_;

+ double height_;

+ double thickness_;

+ Color barkTint_;

+ Color leafTint_;

+ };

+

+数据很多,并且网格和贴图数据还挺大。整个深林的物体在一帧中被扔进去GPU就太多了,所幸的是,有一个很古老的窍门来处理这个。

+关键的是,即便深林中有成千上万的树,它们大部分看起来相似。它们大部分都用同样的网格和贴图。这就意味着远近许多物体间都有着许多共性。

+

+我们通过把物体分块能很明显地模拟这一切,首先,我们取出所有树共有的数据放到一个单独的类:

+

+ class TreeModel

+ {

+ private:

+ Mesh mesh_;

+ Texture bark_;

+ Texture leaves_;

+ };

+游戏只需要一个这样的类,因为没有道理在内存中存有成千上万个同样的网格和贴图。因此,每一个树的实例,都用一个指向共享的TreeModel这个类的引用。这就意味着,在Tree这个类里有这么一个指针:

+

+ class Tree

+ {

+ private:

+ TreeModel* model_;

+

+ Vector position_;

+ double height_;

+ double thickness_;

+ Color barkTint_;

+ Color leafTint_;

+ };

+

+你可以这样形象地描述:

+

+这样能很好的在主内存中存储物体,不过这却对渲染没太大帮助。在树林搬到屏幕上之前,它必须自己搬运到GPU,我们必须用显卡能理解的方式来表达资源共享。

+

+### 一千个实例

\ No newline at end of file

diff --git a/02.3-Observer.md b/02.3-Observer.md

index 12fcbbd..c784ab4 100644

--- a/02.3-Observer.md

+++ b/02.3-Observer.md

@@ -1,2 +1,734 @@

Observer

============================

+

+^title Observer

+^section Design Patterns Revisited

+

+You can't throw a rock at a computer without hitting an application built using

+the [Model-View-Controller][MVC] architecture, and

+underlying that is the Observer pattern. Observer is so pervasive that Java put

+it in its core library ([`java.util.Observer`][java]) and C# baked it right into

+the *language* (the [`event`][event] keyword).

+

+[MVC]: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Model%E2%80%93view%E2%80%93controller

+[java]: http://docs.oracle.com/javase/7/docs/api/java/util/Observer.html

+[event]: http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/8627sbea.aspx

+

+

+

+Observer is one of the most widely used and widely known of the original Gang of

+Four patterns, but the game development world can be strangely cloistered at

+times, so maybe this is all news to you. In case you haven't left the abbey in a

+while, let me walk you through a motivating example.

+

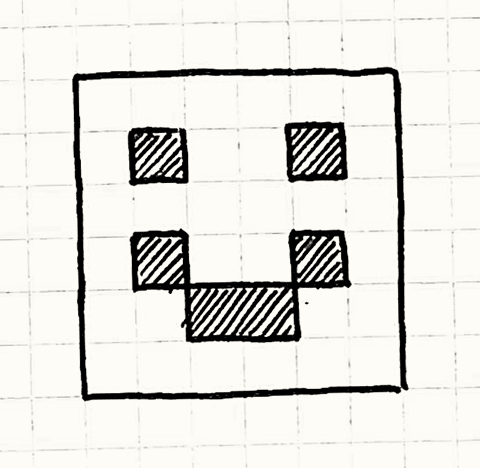

+## Achievement Unlocked

+

+Say we're adding an achievements system to our game.

+It will feature dozens of different badges players can earn for completing

+specific milestones like "Kill 100 Monkey Demons", "Fall off a Bridge", or

+"Complete a Level Wielding Only a Dead Weasel".

+

+

+

+This is tricky to implement cleanly since we have such a wide range of

+achievements that are unlocked by all sorts of different behaviors. If we aren't

+careful, tendrils of our achievement system will twine their way through every

+dark corner of our codebase. Sure, "Fall off a Bridge" is somehow tied to the

+physics engine, but do we really want to see a call

+to `unlockFallOffBridge()` right in the middle of the linear algebra in our

+collision resolution algorithm?

+

+

+

+What we'd like, as always, is to have all the code concerned with one facet of

+the game nicely lumped in one place. The challenge is that achievements are

+triggered by a bunch of different aspects of gameplay. How can that work without

+coupling the achievement code to all of them?

+

+That's what the observer pattern is for. It lets one piece of code announce that

+something interesting happened *without actually caring who receives the

+notification*.

+

+For example, we've got some physics code that handles gravity and tracks which

+bodies are relaxing on nice flat surfaces and which are plummeting toward sure

+demise. To implement the "Fall off a Bridge" badge, we could just jam the

+achievement code right in there, but that's a mess. Instead, we can just do:

+

+^code physics-update

+

+All it does is say, "Uh, I don't know if anyone

+cares, but this thing just fell. Do with that as you will."

+

+

+

+The achievement system registers itself so that whenever the physics code sends

+a notification, the achievement system receives it. It can then check to see if

+the falling body is our less-than-graceful hero, and if his perch prior to this

+new, unpleasant encounter with classical mechanics was a bridge. If so, it

+unlocks the proper achievement with associated fireworks and fanfare, and it

+does all of this with no involvement from the physics code.

+

+In fact, we can change the set of achievements or tear

+out the entire achievement system without touching a line of the physics engine.

+It will still send out its notifications, oblivious to the fact that nothing is

+receiving them anymore.

+

+

+

+## How it Works

+

+If you don't already know how to implement the pattern, you could probably

+guess from the previous description, but to keep things easy on you, I'll walk

+through it quickly.

+

+### The observer

+

+We'll start with the nosy class that wants to know when another object does

+something interesting. These inquisitive objects are defined by this interface:

+

+

+

+^code observer

+

+

+

+Any concrete class that implements this becomes an observer. In our example,

+that's the achievement system, so we'd have something like so:

+

+^code achievement-observer

+

+### The subject

+

+The notification method is invoked by the object being observed. In Gang of Four

+parlance, that object is called the "subject". It has two jobs. First, it holds

+the list of observers that are waiting oh-so-patiently for a missive from it:

+

+

+

+^code subject-list

+

+

+

+The important bit is that the subject exposes a *public* API for modifying that

+list:

+

+^code subject-register

+

+That allows outside code to control who receives notifications. The subject

+communicates with the observers, but it isn't *coupled* to them. In our example,

+no line of physics code will mention achievements. Yet, it can still talk to the

+achievements system. That's the clever part about this pattern.

+

+It's also important that the subject has a *list* of observers instead of a

+single one. It makes sure that observers aren't implicitly coupled to *each

+other*. For example, say the audio engine also observes the fall event so that

+it can play an appropriate sound. If the subject only supported one observer,

+when the audio engine registered itself, that would *un*-register the

+achievements system.

+

+That means those two systems would interfere with each other -- and in a

+particularly nasty way, since the second would disable the first. Supporting a

+list of observers ensures that each observer is treated independently from the

+others. As far as they know, each is the only thing in the world with eyes on

+the subject.

+

+The other job of the subject is sending notifications:

+

+

+

+^code subject-notify

+

+

+

+### Observable physics

+

+Now, we just need to hook all of this into the physics engine so that it can send

+notifications and the achievement system can wire itself up to receive them.

+We'll stay close to the original *Design Patterns* recipe and inherit `Subject`:

+

+^code physics-inherit

+

+This lets us make `notify()` in `Subject` protected. That way the derived

+physics engine class can call it to send notifications, but code outside of it

+cannot. Meanwhile, `addObserver()` and `removeObserver()` are public, so

+anything that can get to the physics system can observe it.

+

+

+

+Now, when the physics engine does something noteworthy, it calls `notify()`

+like in the motivating example before. That walks the observer list and gives

+them all the heads up.

+

+

+

+Pretty simple, right? Just one class that maintains a list of pointers to

+instances of some interface. It's hard to believe that something so

+straightforward is the communication backbone of countless programs and app

+frameworks.

+

+But the Observer pattern isn't without its detractors. When I've asked other

+game programmers what

+they think about this pattern, they bring up a few complaints. Let's see what we

+can do to address them, if anything.

+

+## "It's Too Slow"

+

+I hear this a lot, often from programmers who don't actually know the details of

+the pattern. They have a default assumption that anything that smells like a

+"design pattern" must involve piles of classes and indirection and other

+creative ways of squandering CPU cycles.

+

+The Observer pattern gets a particularly bad rap here because it's been known to

+hang around with some shady characters named "events", "messages", and even "data binding". Some of those systems

+*can* be slow (often deliberately, and for good reason). They involve things

+like queuing or doing dynamic allocation for each notification.

+

+

+

+But, now that you've seen how the pattern is actually implemented, you know that

+isn't the case. Sending a notification is simply walking a list and calling some

+virtual methods. Granted, it's a *bit* slower than a statically dispatched

+call, but that cost is negligible in all but the most performance-critical

+code.

+

+I find this pattern fits best outside of hot code paths anyway, so you can

+usually afford the dynamic dispatch. Aside from that, there's virtually no

+overhead. We aren't allocating objects for messages. There's no queueing. It's

+just an indirection over a synchronous method call.

+

+### It's too *fast?*

+

+In fact, you have to be careful because the Observer pattern *is* synchronous.

+The subject invokes its observers directly, which means it doesn't resume its

+own work until all of the observers have returned from their notification

+methods. A slow observer can block a subject.

+

+This sounds scary, but in practice, it's not the end of the world. It's just

+something you have to be aware of. UI programmers -- who've been doing

+event-based programming like this for ages -- have a time-worn motto for this:

+"stay off the UI thread".

+

+If you're responding to an event synchronously, you need to finish and return

+control as quickly as possible so that the UI doesn't lock up. When you have

+slow work to do, push it onto another thread or a work queue.

+

+You do have to be careful mixing observers with threading and explicit locks,

+though. If an observer tries to grab a lock that the subject has, you can

+deadlock the game. In a highly threaded engine, you may be better off with

+asynchronous communication using an Event Queue.

+

+## "It Does Too Much Dynamic Allocation"

+

+Whole tribes of the programmer clan -- including many game developers -- have

+moved onto garbage collected languages, and dynamic allocation isn't the boogie

+man that it used to be. But for performance-critical software like games, memory

+allocation still matters, even in managed languages. Dynamic allocation takes time, as does reclaiming memory,

+even if it happens automatically.

+

+

+

+In the example code before, I used a fixed array because I'm trying to keep

+things dead simple. In real implementations, the observer list is almost always

+a dynamically allocated collection that grows and shrinks as observers are

+added and removed. That memory churn spooks some people.

+

+Of course, the first thing to notice is that it only allocates memory when

+observers are being wired up. *Sending* a notification requires no memory

+allocation whatsoever -- it's just a method call. If you hook up your observers

+at the start of the game and don't mess with them much, the amount of allocation

+is minimal.

+

+If it's still a problem, though, I'll walk through a way to implement adding and

+removing observers without any dynamic allocation at all.

+

+### Linked observers

+

+In the code we've seen so far, `Subject` owns a list of pointers to each

+`Observer` watching it. The `Observer` class itself has no reference to this

+list. It's just a pure virtual interface. Interfaces are preferred over

+concrete, stateful classes, so that's generally a good thing.

+

+But if we *are* willing to put a bit of state in `Observer`, we can solve our

+allocation problem by threading the subject's list *through the observers

+themselves*. Instead of the subject having a separate collection of pointers,

+the observer objects become nodes in a linked list:

+

+

+

+To implement this, first we'll get rid of the array in `Subject` and replace it

+with a pointer to the head of the list of observers:

+

+^code linked-subject

+

+Then we'll extend `Observer` with a pointer to the next observer in the list:

+

+^code linked-observer

+

+We're also making `Subject` a friend class here. The subject owns the API for adding

+and removing observers, but the list it will be managing is now inside the

+`Observer` class itself. The simplest way to give it the ability to poke at that

+list is by making it a friend.

+

+Registering a new observer is just wiring it into the list. We'll take the easy

+option and insert it at the front:

+

+^code linked-add

+

+The other option is to add it to the end of the linked list. Doing that adds a

+bit more complexity. `Subject` has to either walk the list to find the end or

+keep a separate `tail_` pointer that always points to the last node.

+

+Adding it to the front of the list is simpler, but does have one side effect.

+When we walk the list to send a notification to every observer, the most

+*recently* registered observer gets notified *first*. So if you register

+observers A, B, and C, in that order, they will receive notifications in C, B, A

+order.

+

+In theory, this doesn't matter one way or the other. It's a tenet of good

+observer discipline that two observers observing the same subject should have no

+ordering dependencies relative to each other. If the ordering *does* matter, it

+means those two observers have some subtle coupling that could end up biting

+you.

+

+Let's get removal working:

+

+

+

+^code linked-remove

+

+

+

+Because we have a singly linked list, we have to walk it to find the observer

+we're removing. We'd have to do the same thing if we were using a regular array

+for that matter. If we use a *doubly* linked list, where each observer has a

+pointer to both the observer after it and before it, we can remove an observer

+in constant time. If this were real code, I'd do that.

+

+The only thing left to do is send a notification.

+That's as simple as walking the list:

+

+^code linked-notify

+

+

+

+Not too bad, right? A subject can have as many observers as it wants, without a

+single whiff of dynamic memory. Registering and unregistering is as fast as it

+was with a simple array. We have sacrificed one small feature, though.

+

+Since we are using the observer object itself as a list node, that implies it

+can only be part of one subject's observer list. In other words, an observer can

+only observe a single subject at a time. In a more traditional implementation

+where each subject has its own independent list, an observer can be in more than

+one of them simultaneously.

+

+You may be able to live with that limitation. I find it more common for a

+*subject* to have multiple *observers* than vice versa. If it *is* a problem for

+you, there is another more complex solution you can use that still doesn't

+require dynamic allocation. It's too long to cram into this chapter, but I'll

+sketch it out and let you fill in the blanks...

+

+### A pool of list nodes

+

+Like before, each subject will have a linked list of observers. However, those

+list nodes won't be the observer objects themselves. Instead, they'll be

+separate little "list node" objects that contain a

+pointer to the observer and then a pointer to the next node in the list.

+

+

+

+Since multiple nodes can all point to the same observer, that means an observer

+can be in more than one subject's list at the same time. We're back to being

+able to observe multiple subjects simultaneously.

+

+

+

+The way you avoid dynamic allocation is simple: since all of those nodes are the

+same size and type, you pre-allocate an Object Pool of them. That gives you a fixed-size pile of

+list nodes to work with, and you can use and reuse them as you need without

+having to hit an actual memory allocator.

+

+## Remaining Problems

+

+I think we've banished the three boogie men used to scare people off this

+pattern. As we've seen, it's simple, fast, and can be made to play nice with

+memory management. But does that mean you should use observers all the time?

+

+Now, that's a different question. Like all design patterns, the Observer pattern

+isn't a cure-all. Even when implemented correctly and efficiently, it may not be

+the right solution. The reason design patterns get a bad rap is because people

+apply good patterns to the wrong problem and end up making things worse.

+

+Two challenges remain, one technical and one at something more like the

+maintainability level. We'll do the technical one first because those are always

+easiest.

+

+### Destroying subjects and observers

+

+The sample code we walked through is solid, but it

+side-steps an important issue: what happens when

+you delete a subject or an

+observer? If you carelessly call `delete` on some observer, a subject may still

+have a pointer to it. That's now a dangling pointer into deallocated memory.

+When that subject tries to send a notification, well... let's just say you're

+not going to have a good time.

+

+

+

+Destroying the subject is easier since in most implementations, the observer

+doesn't have any references to it. But even then, sending the subject's bits to

+the memory manager's recycle bin may cause some problems. Those observers may

+still be expecting to receive notifications in the future, and they don't know

+that that will never happen now. They aren't observers at all, really, they just

+think they are.

+

+You can deal with this in a couple of different ways. The simplest is to do what

+I did and just punt on it. It's an observer's job to unregister itself from any

+subjects when it gets deleted. More often than not, the observer *does* know

+which subjects it's observing, so it's usually just a matter of adding a `removeObserver()` call to its destructor.

+

+

+

+If you don't want to leave observers hanging when a subject gives up the ghost,

+that's easy to fix. Just have the subject send one final "dying breath"

+notification right before it gets destroyed. That way, any observer can receive

+that and take whatever action it thinks is

+appropriate.

+

+

+

+People -- even those of us who've spent enough time in the company of machines

+to have some of their precise nature rub off on us -- are reliably terrible at

+being reliable. That's why we invented computers: they don't make the mistakes

+we so often do.

+

+A safer answer is to make observers automatically unregister themselves from

+every subject when they get destroyed. If you implement the logic for that once

+in your base observer class, everyone using it doesn't have to remember to do it

+themselves. This does add some complexity, though. It means each *observer* will

+need a list of the *subjects* it's observing. You end up with pointers going in

+both directions.

+

+### Don't worry, I've got a GC

+

+All you cool kids with your hip modern languages with garbage collectors are

+feeling pretty smug right now. Think you don't have to worry about this because

+you never explicitly delete anything? Think again!

+

+Imagine this: you've got some UI screen that shows a bunch of stats about the

+player's character like their health and stuff. When the player brings up the

+screen, you instantiate a new object for it. When they close it, you just forget

+about the object and let the GC clean it up.

+

+Every time the character takes a punch to the face (or elsewhere, I suppose), it

+sends a notification. The UI screen observes that and updates the little health

+bar. Great. Now what happens when the player dismisses the screen, but you don't

+unregister the observer?

+

+The UI isn't visible anymore, but it won't get garbage collected since the

+character's observer list still has a reference to it. Every time the screen is

+loaded, we add a new instance of it to that increasingly long list.

+

+The entire time the player is playing the game, running around, and getting in

+fights, the character is sending notifications that get received by *all* of

+those screens. They aren't on screen, but they receive notifications and waste

+CPU cycles updating invisible UI elements. If they do other things like play

+sounds, you'll get noticeably wrong behavior.

+

+This is such a common issue in notification systems that it has a name: the

+*lapsed listener problem*. Since subjects retain

+references to their listeners, you can end up with zombie UI objects lingering

+in memory. The lesson here is to be disciplined about unregistration.

+

+

+

+### What's going on?

+

+The other, deeper issue with the Observer pattern is a direct consequence of its

+intended purpose. We use it because it helps us loosen the coupling between two

+pieces of code. It lets a subject indirectly communicate with some observer

+without being statically bound to it.

+

+This is a real win when you're trying to reason about the subject's behavior,

+and any hangers-on would be an annoying distraction. If you're poking at the

+physics engine, you really don't want your editor -- or your mind -- cluttered

+up with a bunch of stuff about achievements.

+

+On the other hand, if your program isn't working and the bug spans some chain of

+observers, reasoning about that communication flow is much more difficult. With

+an explicit coupling, it's as easy as looking up the method being called. This

+is child's play for your average IDE since the coupling is static.

+

+But if that coupling happens through an observer list, the only way to tell who

+will get notified is by seeing which observers happen to be in that list *at

+runtime*. Instead of being able to *statically* reason about the communication

+structure of the program, you have to reason about its *imperative, dynamic*

+behavior.

+

+My guideline for how to cope with this is pretty simple. If you often need to

+think about *both* sides of some communication in order to understand a part of

+the program, don't use the Observer pattern to express that linkage. Prefer

+something more explicit.

+

+When you're hacking on some big program, you tend to have lumps of it that you

+work on all together. We have lots of terminology for this like "separation of

+concerns" and "coherence and cohesion" and "modularity", but it boils down to

+"this stuff goes together and doesn't go with this other stuff".

+

+The observer pattern is a great way to let those mostly unrelated lumps talk to

+each other without them merging into one big lump. It's less useful *within* a

+single lump of code dedicated to one feature or aspect.

+

+That's why it fits our example well: achievements and physics are almost entirely

+unrelated domains, likely implemented by different people. We want the bare

+minimum of communication between them so that working on either one doesn't

+require much knowledge of the other.

+

+## Observers Today

+

+*Design Patterns* came out in the 90s. Back then,

+object-oriented programming was *the* hot paradigm. Every programmer on Earth

+wanted to "Learn OOP in 30 Days," and middle managers paid them based on the

+number of classes they created. Engineers judged their mettle by the depth of

+their inheritance hierarchies.

+

+

+

+The Observer pattern got popular during that zeitgeist, so it's no surprise that

+it's class-heavy. But mainstream coders now are more comfortable with functional

+programming. Having to implement an entire interface just to receive a

+notification doesn't fit today's aesthetic.

+

+It feels heavyweight and rigid. It *is*

+heavyweight and rigid. For example, you can't have a single class that uses

+different notification methods for different subjects.

+

+

+

+A more modern approach is for an "observer" to be only a reference to a method

+or function. In languages with first-class functions, and especially ones with

+closures, this is a much more common way to do

+observers.

+

+

+

+For example, C# has "events" baked into the language. With those, the observer

+you register is a "delegate", which is that language's term for a reference to a

+method. In JavaScript's event system, observers *can* be objects supporting a

+special `EventListener` protocol, but they can also just be functions. The

+latter is almost always what people use.

+

+If I were designing an observer system today, I'd make it function-based instead of class-based. Even in C++, I

+would tend toward a system that let you register member function pointers as

+observers instead of instances of some `Observer` interface.

+

+

+

+## Observers Tomorrow

+

+Event systems and other observer-like patterns are incredibly common these days.

+They're a well-worn path. But if you write a few large apps using them, you

+start to notice something. A lot of the code in your observers ends up looking

+the same. It's usually something like:

+

+ 1. Get notified that some state has changed.

+

+ 2. Imperatively modify some chunk of UI to reflect the new state.

+

+It's all, "Oh, the hero health is 7 now? Let me set the width of the health bar

+to 70 pixels." After a while, that gets pretty tedious. Computer science

+academics and software engineers have been trying to eliminate that tedium for a

+*long* time. Their attempts have gone under a number of different names:

+"dataflow programming", "functional reactive programming", etc.

+

+While there have been some successes, usually in limited domains like audio

+processing or chip design, the Holy Grail still hasn't been found. In the

+meantime, a less ambitious approach has started gaining traction. Many recent

+application frameworks now use "data binding".

+

+Unlike more radical models, data binding doesn't try to entirely eliminate

+imperative code and doesn't try to architect your entire application around a

+giant declarative dataflow graph. What it does do is automate the busywork where

+you're tweaking a UI element or calculated property to reflect a change to some

+value.

+

+Like other declarative systems, data binding is probably a bit too slow and

+complex to fit inside the core of a game engine. But I would be surprised if I

+didn't see it start making inroads into less critical areas of the game like

+UI.

+

+In the meantime, the good old Observer pattern will still be here waiting for

+us. Sure, it's not as exciting as some hot technique that manages to cram both

+"functional" and "reactive" in its name, but it's dead simple and it works. To

+me, those are often the two most important criteria for a solution.

\ No newline at end of file

diff --git a/02.4-Prototype.md b/02.4-Prototype.md

index bb74e02..45c921c 100644

--- a/02.4-Prototype.md

+++ b/02.4-Prototype.md

@@ -1,2 +1,611 @@

Prototype

============================

+

+^title Prototype

+^section Design Patterns Revisited

+

+The first time I heard the word "prototype" was in *Design Patterns*. Today, it

+seems like everyone is saying it, but it turns out they aren't talking about the

+design pattern. We'll cover that here, but I'll also

+show you other, more interesting places where the term "prototype" and the

+concepts behind it have popped up. But first, let's revisit the original pattern.

+

+

+

+## The Prototype Design Pattern

+

+Pretend we're making a game in the style of Gauntlet. We've got creatures and

+fiends swarming around the hero, vying for their share of his flesh. These

+unsavory dinner companions enter the arena by way of "spawners", and there is a

+different spawner for each kind of enemy.

+

+For the sake of this example, let's say we have different classes for each kind

+of monster in the game -- `Ghost`, `Demon`, `Sorcerer`, etc., like:

+

+^code monster-classes

+

+A spawner constructs instances of one particular monster type. To support every

+monster in the game, we *could* brute-force it by having a spawner class for

+each monster class, leading to a parallel class hierarchy:

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+Implementing it would look like this:

+

+^code spawner-classes

+

+Unless you get paid by the line of code, this is obviously not a fun way

+to hack this together. Lots of classes, lots of boilerplate, lots of redundancy,

+lots of duplication, lots of repeating myself...

+

+The Prototype pattern offers a solution. The key idea is that *an object can

+spawn other objects similar to itself*. If you have one ghost, you can make more

+ghosts from it. If you have a demon, you can make other demons. Any monster can

+be treated as a *prototypal* monster used to generate other versions of

+itself.

+

+To implement this, we give our base class, `Monster`, an abstract `clone()`

+method:

+

+^code virtual-clone

+

+Each monster subclass provides an implementation that returns a new object

+identical in class and state to itself. For example:

+

+^code clone-ghost

+

+Once all our monsters support that, we no longer need a spawner class for each

+monster class. Instead, we define a single one:

+

+^code spawner-clone

+

+It internally holds a monster, a hidden one whose sole purpose is to be used by

+the spawner as a template to stamp out more monsters like it, sort of like a

+queen bee who never leaves the hive.

+

+

+

+To create a ghost spawner, we create a prototypal ghost instance and

+then create a spawner holding that prototype:

+

+^code spawn-ghost-clone

+

+One neat part about this pattern is that it doesn't just clone the *class* of

+the prototype, it clones its *state* too. This means we could make a spawner for

+fast ghosts, weak ghosts, or slow ghosts just by creating an appropriate

+prototype ghost.

+

+I find something both elegant and yet surprising about this pattern. I can't

+imagine coming up with it myself, but I can't imagine *not* knowing about it now

+that I do.

+

+### How well does it work?

+

+Well, we don't have to create a separate spawner class for each monster, so

+that's good. But we *do* have to implement `clone()` in each monster class.

+That's just about as much code as the spawners.

+

+There are also some nasty semantic ratholes when you sit down to try to write a

+correct `clone()`. Does it do a deep clone or shallow one? In other words, if a

+demon is holding a pitchfork, does cloning the demon clone the pitchfork too?

+

+Also, not only does this not look like it's saving us much code in this

+contrived problem, there's the fact that it's a *contrived problem*. We had to

+take as a given that we have separate classes for each monster. These days,

+that's definitely *not* the way most game engines roll.

+

+Most of us learned the hard way that big class hierarchies like this are a pain

+to manage, which is why we instead use patterns like Component and Type Object to model different kinds of entities without

+enshrining each in its own class.

+

+### Spawn functions

+

+Even if we do have different classes for each monster, there are other ways to