Impact of TAs on rates of compliance for UKRI OA policy and Open Access flavours for UKRI-funded publications

Pablo de Castro, Open Access Advocacy Librarian at U Strathclyde

As of Year 10 (1 Apr 2022-31 Mar 2023) the UKRI have ceased to require the annual reporting on both expenditure and OA flavour of their funded publications that was mandatory in previous years. The reasons for this have not been made known – though there are ongoing attempts at automating the reporting in both areas. At a time when the OA landscape seems again to be in flux, we thought it would make sense to keep examining the evolution of this Gold vs Green OA distribution for UKRI-funded publications at Strathclyde.

This is because the impact of the Read & Publish deals (aka Transformative Agreements or TAs) is growing as an increasing number of them come into operation – see table 1 at the bottom of this post showing the kick-off timing for the various R&P deals we have at Strathclyde. The regular monitoring of the uptake for these R&P deals at Strathclyde does in fact show that the “most popular” R&P deal (meaning the one with the highest uptake in terms of the number of articles published Gold OA) is the Elsevier one. Given that this agreement only kicked-off in Mar 2022, this means that the impact of this specific agreement on the rate of Gold OA publications was not captured in the previous round of UKRI reporting (Year 9). It also means that the percentage of Gold OA UKRI-funded publications at Strathclyde could be expected to have experienced a significant increase again in the Year 9 to Year 10 transition.

The figures reported in this post are Strathclyde’s alone and as such not too statistically significant due to the limited size of the sample. However, given that R&P deals are typically signed by all UK universities as a consortium, the same impact on the rise of Gold OA seen at Strathclyde could be expected to have happened in every other HEI in the country. It would be useful however to have the actual figures for at least a few other institutions to confirm this trend. This will also eventually show on the CWTS Leiden ranking of worldwide institutions by percentage of their outputs that are openly available – a ranking in which UK universities overwhelmingly sit in the top-100 positions mainly thanks to the REF2021 OA policy that makes Green OA mandatory.

Fig 1. CWTS Leiden ranking by percentage of openly available institutional publications: 23 out of the 25 universities with over 90% Open Access are in the UK

However, because this CWTS Leiden ranking is based on the aggregation of several years and because it covers all institutional research outputs, the effect of R&P deals on research outputs funded by a specific cOAlition S-member funder may be harder to spot there. Restricting the OA flavour analysis to UKRI-funded publications and comparing it across recent years is the best way to surface the impact of R&P deals especially given that the UKRI have for quite some time expressed a preference for Gold OA in their Open Access policy.

It’s not the purpose of this piece to pass any judgement on R&P agreements, but rather to show their impact. It is worth saying however that despite some widespread criticism of the possible geographic inequalities and vendor lock-in mechanisms embedded in these agreements with publishers, from a strict institutional OA practitioner perspective their availability has made our lives *much* easier. TAs are very helpful when expected to maintain an over 90% rate of institutional Open Access availability as most UK HEIs are doing as per the figures shown on the CWTS Leiden OA ranking above. One of the reasons is that receiving automated notifications upon manuscript acceptance by the publisher instead of relying on the author to create a record for the newly accepted journal article or conference paper in the institutional system means a massive simplification of the monitoring workflow for institutional publications. One has previously written somewhere that this model fits OA landscapes particularly well where the homework (meaning very high rates of Green OA deposit of accepted manuscripts) was previously done. Rather than on the business model itself, the main advantage of a TA-based approach lies in an efficient collaboration between institutions and publishers that it makes possible (frequent conflicts notwithstanding).

A couple of methodological caveats are de rigueur before focusing on the figures. First, the identification of in-scope annual UKRI-funded publications is based on a Scopus search and on the date of first online release for the publications. This makes it necessary for the checking process to be manually conducted, given that the international literature database does not include such date in the metadata it offers for the publications. The upside of the time-consuming manual checks is that they also allow to identify any missing reference in the institutional system (usually due to authors not having created the mandatory Pure records in the first place).

The Open Access team has developed a number of strategies over the years to keep the missing references for publications to the bare minimum, including the analysis of the (often redundant) Jisc Publications Router feed and the periodic checks for UKRI-funded outputs in Scopus. Despite these attempts at catching all publications produced at the institution, the number of missing references identified in the course of the annual analysis remains stubbornly high – no fewer than 25 Pure records were missing from the 530-strong sample for the UKRI Year 10.

Second, the funding references have traditionally been a difficult area to address. Scopus has massively improved the quality of the metadata on funding acknowledgements – thanks at least partially to the more comprehensive data-providing workflows that authors are required to follow upon manuscript submission, and this is in fact another aspect where R&P deals are proving useful. However, there are intractable elements in this area from a literature database perspective. If authors include a reference in their manuscript to a specific UKRI Research Council, the ensuing publication will be included on the list of UKRI-funded publications provided by Scopus even if more often than not there is no grant number in these funding references (see an example in the figure below). This inevitably means a degree of inaccuracy in the identification of UKRI-funded publications, but given the size of the sample, it doesn’t significantly impact the general trend in the evolution of Gold OA publications.

Fig 2. Funding acknowledgements for a publication mistakenly identified as UKRI-funded

The figures

The analysis of the OA flavours for UKRI-funded publications produced at Strathclyde during consecutive years as defined by the funder (UK fiscal years, i.e. in the case of Year 10 from 1 Apr 2022 to 31 Mar 2023) has focused on the last three years. This is because the methodology described above has consistently been used in this period (meaning the same Scopus queries and a homogeneous no-hybrid policy) and also – especially – because the arrival of R&P deals has mostly taken place during these three years.

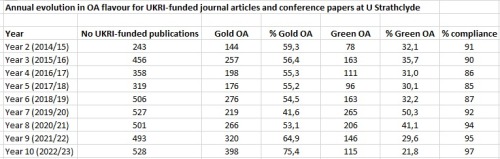

The last three years have unsurprisingly seen a sustained increase in the rates of Gold OA: from Year 8 to Year 9 there was a 12 percentage point increase in the rate of Gold OA UKRI-funded journal articles and conference papers, and the figures for Year 10 show another 10.5-point increase in the Gold OA percentage. At the same time, Green OA percentages saw a 11.5-point decrease from Year 8 to Year 9 and a further 8 percentage point decrease in Year 10.

Also worth noting is how the aggregated levels of compliance with the UKRI OA policy have increased alongside the growth of Gold OA. The workflow for approving Gold OA for an accepted manuscript under a specific R&P deal requires the intervention of the library, and the library makes the availability of a publication record with the full-text accepted manuscript in the institutional CRIS a prerequisite for the approval of the Gold OA request. This means that publications are much more likely to meet the funder’s OA policy than when solely based on the eligibility for the REF assessment exercise (which many publications do not aspire to anyway). This is yet another aspect where TAs are benefitting the labour-intensive institutional work to make sure all publications are recorded in the system and meet the funder requirements, including keeping them eligible for the REF.

A new area that this manual analysis allows an insight into is the application of Plan S-aligned rights retention policies. These are defined as ‘route 2’ in the UKRI OA policy that came into force (for manuscripts submitted) on 1 Apr 2022. An analysis of OA publication patterns covering from 1 Apr 2022 to 31 Mar 2023 will therefore inevitably include a significant number of Green OA articles and conference papers were the rights retention statement has been applied or should have been applied.

A cursory look at this aspect when checking the Green OA compliance shows that a good number of academics that needed to include the 2-line rights retention statement in their manuscript acknowledgements as required by the UKRI have done so. On the other hand, there are many publications where this approach was not followed even though it should have been. This will require a deeper analysis as manuscript submission dates are not always available in the publication records, but it’s a valuable insight at a time when an Institutional Rights Retention Policy (IRRP) is in preparation at Strathclyde Uni that will make this 'route 2’ the default approach for all institutional publications regardless of their funding acknowledgements.

From the generic examination of the reasons for non-compliant Green OA (meaning where the rights retention statement has not been included), the most conspicuous one is the non-corresponding authorship. Where Strathclyde researchers are not the lead authors, it’s notoriously difficult for them to persuade the rest of co-authors that this 2-line statement should be included in the manuscripts when it’s effectively meaningless (if not problematic) for everyone else. This issue may be mitigated where the corresponding author is at another UK university, since many of them have now adopted an IRRP and the UKRI OA policy applies everywhere in the UK anyway. When the corresponding author is abroad though, especially in countries like China or the US, and most other co-authors are also abroad, this becomes a real problem. There is a Jisc working group examining the challenges of non-corresponding authorships (also from the perspective of the application of TAs) that may be able to figure out a way to address this issue around compliance with funders’ OA policies.

The UKRI (and the Wellcome Trust) being a cOAlition S member, another key issue is the cOAlition S announcement earlier this year that TAs will cease to be supported at the end of 2024. Given the degree of reliance on TAs that the figures above reveal for the purpose of complying with the UKRI OA policy via its 'Route 1’, the discontinuation of the financial support for these instruments would mean a fundamental change in the approach to OA implementation at institutions. This is because most of the funding for TAs in the UK is currently coming from the Open Access block grants that the UKRI allocate to UK institutions. This is not necessarily the case in other European countries, where research-performing organisations have sometimes managed to organise themselves to collectively cover the expenses for these TAs by pooling up contributions from their own institutional budgets. However, this is not an arrangement that has been considered in the UK, where the research funder-provided block grant model has been in place for 10 years now.

This poses a potential risk of post-2024 OA landscape fragmentation across countries and even within cOAlition S itself. In the UK, the rapid development of IRRPs seems a reflex reaction to the possible discontinuation of TAs, which are generally contested as financially difficult to sustain by budget-constrained institutions that are not seeing any decrease in subscription costs. This shift in OA implementation focus from TA-enabled Gold OA to immediate Green OA would involve however a cultural change for researchers that may not always be easy to argue for given how used they have become to straightforward Gold OA. The widely expected inclusion of the rights retention strategy as a requirement in the forthcoming REF OA policy would massively support this Plan S-aligned transition to immediate Green OA, but significant hurdles would still exist that would need to be overcome.

Regardless of the way forward that OA implementation ends up taking, the analysis of the OA flavour of institutional UKRI-funded outputs is a very valuable tool to assess how successfully different OA policy instruments are being implemented. It is expected that these reflections may drive other institutions to also carry out this analysis even if no longer mandated by the funder.

Note.- While discussing these UKRI Year 8 to Year 10 figures with Helen Young, Head of Research Policy and Information within Strathclyde’s Research and Knowledge Exchange Services, she suggested that it would be interesting to also have a look at the figures for previous years. Since the UKRI required these to be included in the annual reports that institutions had to submit, she argued that it should be possible to dig them up. These older figures have now been retrieved back to Year 2 (which is as far back as we have data for) and the results are shown below. It’s worth mentioning that unusually high Gold OA rates in earlier years are mostly due to the fact that APCs were still being paid for manuscripts accepted in hybrid journals as a way to absorb a significant block grant underspend that was carried over from one exercise to the next for several years.

Table 1. Year(s) the currently available R&P deals at U Strathclyde became operational