Abstract

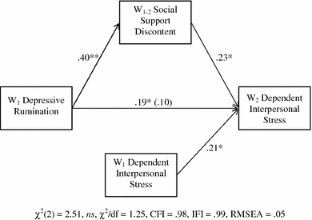

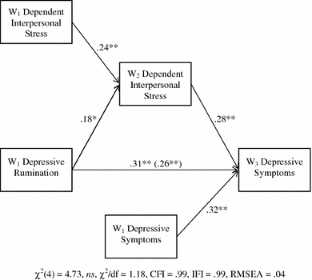

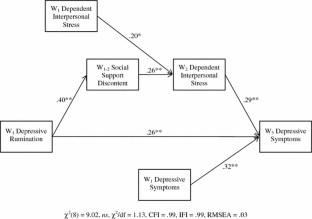

This research examined an integration of cognitive and interpersonal theories of depression by investigating the prospective contribution of depressive rumination to perceptions of social support, the generation of interpersonal stress, and depressive symptoms. It was hypothesized that depressive ruminators would generate stress in their relationships, and that social support discontent would account for this association. Further, depressive rumination and dependent interpersonal stress were examined as joint and unique predictors of depressive symptoms over time. Participants included 122 undergraduate students (M age = 19.78 years, SD = 3.54) who completed assessments of depressive rumination, perceptions of social support, life stress, and depressive symptoms across three waves, each spaced 9 months apart. Results revealed that social support discontent accounted for the prospective association between depressive rumination and dependent interpersonal stress, and that both depressive rumination and dependent interpersonal stress contributed to elevations in depressive symptoms over time. These findings highlight the complex interplay between cognitive and interpersonal processes that confer vulnerability to depression, and have implications for the development of integrated depression-focused intervention endeavors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

To investigate whether cognitive risk status influenced any patterns of effects, supplemental path analyses were conducted that controlled for cognitive risk status. Including cognitive risk status did not alter the significance of the paths between any of the key study variables, and significantly decreased the strength of the model fit indices. Accordingly, the reported results do not adjust for cognitive risk status.

Interpersonal events reflecting perceptions of social support were removed from analyses due to content overlap with social support discontent (i.e., “Had no one to confide in,” “Had fewer friends than would like or rarely sought out by others for activities,” “Rarely received affection, respect, or interest from friends,” “Live alone and see other people less often than would like”).

References

Abela, J. R. Z., Vanderbilt, E., & Rochon, A. (2004). A test of the integration of the response styles and social support theories of depression in third and seventh grade children. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23, 653–674.

Abramson, L. Y., Metalsky, G. I., & Alloy, L. B. (1989). Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review, 96, 358–372.

Adams, P., Abela, J. R. Z., & Hankin, B. L. (2007). Factorial categorization of depression-related constructs in early adolescents. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly, 21, 123–139.

Alloy, L. B., & Abramson, L. Y. (1999). The temple-wisconsin cognitive vulnerability to depression (CVD) project: Conceptual background, design, and methods. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly, 13, 227–262.

Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Hogan, M. E., Whitehouse, W. G., Rose, D. T., Robinson, M. S., et al. (2000). The temple-wisconsin cognitive vulnerability to depression project: Lifetime history of Axis I psychopathology in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 403–418.

Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Walshaw, P. D., & Nereen, A. M. (2006a). Cognitive vulnerability to unipolar and bipolar mood disorders. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 25, 726–754.

Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Whitehouse, W. G., Hogan, M. E., Panzarella, C., & Rose, D. T. (2006b). Prospective incidence of first onsets and recurrences of depression in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115, 145–156.

Alloy, L. B., & Clements, C. M. (1992). Illusion of control: Invulnerability to negative affect and depressive symptoms after laboratory and natural stressors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101, 234–245.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression: Clinical, experimental, and theoretical aspects. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York, NY: Guilford.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Garbin, M. G. (1988). Psychometric properties of the beck depression inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 8, 77–100.

Bottonari, K. A., Roberts, J. E., Kelly, M. A. R., Kashdan, T. B., & Ciesla, J. A. (2007). A prospective investigation of the impact of attachment style on stress generation among clinically depressed individuals. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 179–188.

Brown, S. D., Alpert, D., Lent, R. W., Hunt, G., & Brady, T. (1988). Perceived social support among college students: Factor structure of the Social Support Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 35, 472–478.

Brown, S. D., Brady, T., Lent, R. W., Wolfert, J., & Hall, S. (1987). Perceived social support among college students: Three studies of the psychometric characteristics and counseling uses of the social support inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 34, 337–354.

Coyne, J. C. (1976). Depression and the response of others. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 85, 186–193.

Daley, S. E., Hammen, C., Burge, D., Davila, J., Paley, B., Lindberg, N., et al. (1997). Predictors of the generation of episodic stress: A longitudinal study of late adolescent women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106, 251–259.

Daley, S. E., Rizzo, C. J., & Gunderson, B. H. (2006). The longitudinal relation between personality disorder symptoms and depression in adolescence: The mediating role of interpersonal stress. Journal of Personality Disorders, 20, 352–368.

Davila, J., Hammen, C., Burge, D., Paley, B., & Daley, S. E. (1995). Poor interpersonal problem solving as a mechanism of stress generation in depression among adolescent women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104, 592–600.

Endicott, J., & Spitzer, R. L. (1978). A diagnostic interview: The schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 35, 837–844.

Flynn, M., & Rudolph, K. D. (2008). Stress generation and adolescent depression: Predictive contribution of maladaptive responses to interpersonal stress. Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence, Chicago, IL.

Haeffel, G., Gibb, B. E., Metalsky, G. I., Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Hankin, B. L., et al. (2008). Measuring cognitive vulnerability to depression: Development and validation of the cognitive style questionnaire. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 824–836.

Hammen, C. (1991). Depression runs in families: The social context of risk and resilience in children of depressed mothers. New York, NY: Springer.

Hammen, C. (1992). Cognitive, life stress, and interpersonal approaches to a developmental psychopathology model of depression. Development and Psychopathology, 4, 191–208.

Hammen, C. (2006). Stress generation in depression: Reflections on origins, research, and future directions. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62, 1065–1082.

Hankin, B. L., Kassel, J. D., & Abela, J. R. Z. (2005). Adult attachment dimensions and specificity of emotional distress symptoms: Prospective investigations of cognitive risk and interpersonal stress generation as mediating mechanisms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 136–151.

Joiner, T. (2000). Depression’s vicious scree: Self-propagating and erosive processes in depression chronicity. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice, 7, 203–218.

Joiner, T., & Coyne, J. C. (1999). The interactional nature of depression. Washington, DC: APA.

Just, N., & Alloy, L. B. (1997). The response styles theory of depression: Tests and an extension of the theory. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106, 221–229.

Lyubomirsky, S., Caldwell, N. D., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1998). Effects of ruminative and distracting responses to depressed mood on retrieval of autobiographical memories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 166–177.

Lyubomirsky, S., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1993). Self-perpetuating properties of dysphoric rumination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 339–349.

Lyubomirsky, S., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1995). Effects of self-focused rumination on negative thinking and interpersonal problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 176–190.

Multon, K. D., & Brown, S. D. (1987). A preliminary manual for the social support inventory (SSI). Chicago: Loyola University of Chicago, Department of Counseling and Educational Psychology.

Needles, D. J., & Abramson, L. Y. (1990). Positive life events, attributional style, and hopefulness: Testing a model of recovery from depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 99, 156–165.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 569–582.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 504–511.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Davis, C. G. (1999). “Thanks for sharing that”: Ruminators and their social support networks. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 801–814.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Morrow, J. (1991). A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 115–121.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Parker, L. E., & Larson, J. (1994). Ruminative coping with depressed mood following loss. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 92–104.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 400–424.

Pennebaker, J. W. (1989). Opening up: The healing power of confiding in others. New York, NY: Morrow.

Pennebaker, J. W. (1993). Putting stress into words: Health, linguistic, and therapeutic implications. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 31, 539–548.

Potthoff, J. G., Holahan, C. J., & Joiner, T. E. (1995). Reassurance seeking, stress generation, and depressive symptoms: An integrative model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 664–670.

Prinstein, M. J., Borelli, J. L., Cheah, C. S. L., Simon, V. A., & Aikins, J. W. (2005). Adolescent girls’ interpersonal vulnerability to depressive symptoms: A longitudinal examination of reassurance-seeking and peer relationships. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114, 676–688.

Rudolph, K. D. (2002). Gender differences in emotional responses to interpersonal stress during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 30, 3–13.

Rudolph, K. D., Flynn, M., & Abaied, J. L. (2007). A developmental perspective on interpersonal theories of youth depression. In J. R. Z. Abela & B. L. Hankin (Eds.), Child and adolescent depression: Causes, treatment, and prevention (pp. 79–102). New York, NY: Guilford.

Rudolph, K. D., Flynn, M., Abaied, J. L., Groot, A. K., & Thompson, R. J. (2009). Why is past depression the best predictor of future depression? Stress generation as a mechanism of depression continuity in girls. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 38, 473–485.

Safford, S. M., Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., & Crossfield, A. G. (2007). Negative cognitive style as a predictor of negative life events in depression-prone individuals: A test of the stress-generation hypothesis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 99, 147–154.

Selby, E. A., Anestis, M. D., & Joiner, T. E. (2008). Understanding the relationship between emotional and behavioral dysregulation: Emotional cascades. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46, 593–611.

Shih, J. H. (2006). Sex differences in stress generation: An examination of sociotropy/autonomy, stress, and depressive symptoms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 434–446.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445.

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In S. Leinhart (Ed.), Sociological methodology 1982 (pp. 290–312). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Sobel, M. E. (1986). Some new results on indirect effects and their standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In N. Tuma (Ed.), Sociological methodology 1986 (pp. 159–186). Washington, DC: American Sociological Association.

Spasojevic, J., & Alloy, L. B. (2001). Rumination as a common mechanism relating depressive risk factors to depression. Emotion, 1, 25–37.

Spasojevic, J., Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., MacCoon, D. G., & Robinson, M. S. (2003). Reactive rumination: Outcomes, mechanisms, and developmental antecedents. In C. Papageorgiou & A. Wells (Eds.), Depressive rumination: Nature, theory and treatment (pp. 43–58). New York, NY: Wiley.

Weinstock, L. M., & Whisman, M. A. (2007). Rumination and excessive reassurance-seeking in depression: A cognitive-interpersonal integration. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 31, 333–342.

Weisman, A., & Beck, A. T. (1978). Development and validation of the Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale: A preliminary investigation. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Flynn, M., Kecmanovic, J. & Alloy, L.B. An Examination of Integrated Cognitive-Interpersonal Vulnerability to Depression: The Role of Rumination, Perceived Social Support, and Interpersonal Stress Generation. Cogn Ther Res 34, 456–466 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-010-9300-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-010-9300-8